The Genocide Museum in Yerevan hosted an exhibition that is titled “Armenian Sport and Gymnastics in the Ottoman Empire”. The museum director Hayk Demoyan, who wrote a book bearing the same title with the exhibition, and 80-years-old grandson of Shavarsh Qrisian, who were issuing Marmnamarz magazine during Ottoman period and exiled to Ayash in 1915, attended the opening of the exhibition. Alin Ozinian, by way of this exhibition, observes how the Armenians’ contribution to the sports culture of these lands was excluded from the official history and she makes room for a reckoning that is related to remembrance, oblivion and forgiveness.

In the official historical texts in Turkey, it is told that, in Ottoman period, the “modern football” was begun to be played in the late 19th century and with the foundation of the republic in 1923, it developed within the framework of “westernization”. These texts swiftly jump to the period of “three big teams” right from 19th century. If there is a gap in the chronology, there must be something interesting to be found; we got used to this. On the lost pages of the “official football”, there are plenty of traces that belong to ourselves and to Armenians.

Football is begun to be played in 1875 by the English people who live in Thessaloniki ,and from there, it spreads to Bornova and Symirnia. The team in Symirnia, which consists of Christians, has many Armenian players. Shavarsh Qrisian, who is frequently mentioned in the Armenian sports history, founds the first Armenian football team “Baltalimanı” in 1905. In the same year, Vahan Cheraz, completing his education in England, returns with a football and the team consisting of the students of Getronagan High School, which he also went, becomes a professional team called “Santral”. With the initiation of Kapriel Macaryan, Dikran Kholayan and many others, professional teams are established that bear the names of the Armenian districts like Üsküdar, Bakırköy, Galata, Kumkapı, Nişantaşı, Şişli, Pera, Kadıköy, Balat, Üsküdar, Kazlıçeşme, Pangaltı, Kınalıada. In addition to Dork, Araks A, Araks B, Ararat, Kilikia, Sasun, Raffi, Demokrat; Armenian high schools like Esayan, Berberyan, Sahakyan, Mıkhitaryan and Armenians from Robert College establish teams; all these teams compete in “Rumeli League” in 1911.

Beside Istanbul, there are over 100 “Armenian football teams” and student clubs in cities like Kütahya, Adapazarı, Trabzon, Adana, Harput, Kars, and especially in Symirnia. Most of this information was published in 1911 in “Marmnamarz” (athletics) magazine edited by Shavarsh Qrisian, which was the first sports periodical of Ottoman period. The magazine had an office in Bahçekapı. This lasted for only 3 years. After the death of Krisyan, who was in the first Armenian group that was exiled to Ayash in 1915, this magazine also vanished.

Sports Exhibition in the Museum

In the recent weeks, while I was at the opening of the exhibition that is titled “Armenian Sport and Gymnastics in the Ottoman Empire” in the temporary exhibitions hall of the Genocide Museum in Yerevan, all these events flashed before my eyes. Shavarsh Qrisian was one of the keynote speakers. Dr. Krisyan, the 80-years-old nephew of Şavaşr Krisyan, was before us; his uncle is engraved in the memories of many researchers as “the man who can send magazines to Europe with the subscription system 100 years ago.” Nephew Krisyan lost his uncle because of the genocide and he has never met him, and he was talking about his uncle, who was murdered when he was at his twenties, as if he is his grandson, not his uncle. His speech was really touching; he talked about the importance of existing and the burden and responsibility of being a child of a community which was tried to be annihilated. He gave some examples concerning the role of Armenians in Ottoman sports culture.

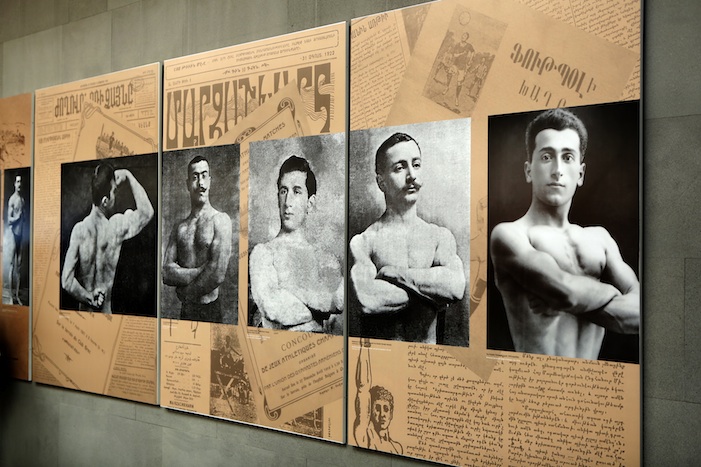

This exhibition that is based on Haky Demoyan’s book “Armenian Sport and Gymnastics in the Ottoman Empire”, which he wrote in 2009 and enriched with thousands of documents and photographs this year, has 12 sections. At the opening, we learned that the most of the visual material was donated to the museum by the families of Grigor Chololyan and Shavarsh Qrisian. Demoyan said that they are working on the Turkish translation of the book and they might take this exhibition to Turkey.

Grandchildren of Vahan Cheraz

At the opening, there are many people from Diaspora. Relatives of Çololyan, Krisyan and even Cheraz were there. The visual material was quite impressive. Sometimes, there is an unimaginable difference between hearing or reading something and seeing it. This was one of those times: the photos of the young athletes with shorts in Merzifon in 1915… This was almost the same feeling that I had, when I was turning the pages of Osman Köker’s book; in his book, he tells the stories of the Armenians who lived in Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century with postcards that were sent between 1900-1914. We already had some information about the Armenian cities, towns and villages; the role that Armenians played in the economic and social life of their settlements; churches, monasteries and schools that belong to Armenians; their newspapers and magazines… We know all of that, but a girl in a postcard, who looks at you from the window of a girls’ school, has the power to wreck everything that you think you got over. All those things that you have read for years couldn’t cause such a great impact. The questions like “What happened to that girl? How was she murdered?” would haunt you for a long time.

The Second Constitutionalist Period

There was something similar in this exhibition. A voice “outside the history” that is similar to what you hear and see was whispering things into your ear as if it tries to keep pace with the exhibition. First, it said that The Second Constitutionalist Period, which promised “freedom” to all people in Ottoman Empire and welcomed with enthusiasm and joy by Armenians, was a deception for Armenian people in all respects. The voice reminded that the “legendary” people like Talat Paşa and Ziya Gökalp, who was one of “ideologists” of the Unionists and one of the famous “Turkists”, were trying to make football “Turkish”; that non-Muslims were dominant in football only because the sultan was preventing Turkish people from engaging in football with the fear that they might be get organized, and they were trying to popularize football among Turkish people; that the names of teams were made Turkish, while Armenians were dreaming that all the oppression in Ottoman Empire will come to an end and a new period will begin with the Unionists… It seemed as if the people in the hall were asking, “What was the real purpose of ‘Ottoman Power Associations’ that was founded by Ziya Gökalp and Enver Paşa and ‘Turkish Power Association’ that was founded by Selim Sırrı, who also initiated the ‘National Olympics Committee’ in 1908?”; though we all know the answer: they wanted to clean the “harmful elements” in sports and make it “Turkish”, and this was also their wish for their new country they were about to establish. Demoyan said: “During that period, football was common in Armenian, Greek and Jewish communities, but they also attached importance to wrestling, boxing, tennis and athletics and they were establishing teams in those fields too.” He also told that Vahram Papazyan and Mıgırdiç Mıgıryan represented Turkey in Stockholm Olympics in 1912.

However, the story is not as innocent as Demoyan told. In 1912, people are not interested in sports because of prejudices and Ottoman Empire isn’t attending Olympics though it is invited, so the athletes who will be attending Olympics are determined by newspaper ads: “Looking for athletes to attend the competitions in Sweden’s capital. Those who are interested can apply to Selim Sırrı Bey (the head of Ottoman Olympics Association).” Two Armenians, Vahram Papazyan and Mıgırdıç Mıgıryan see the ad and make an application. However, when Selim Sırrı learns the names of these young athletes, he gives a “strange” response saying that the participants should pay out of their pocket to go to Stockholm. The intention is obvious: “Since the sports cannot be nationalized, Armenians should cover their own expenses.” With the help of Ardavazt Sports Club, two athletes manage to overcome obstacles and collect enough money to go to Olympics. When they see that there is no Ottoman flag in the Olympics area, they run to ambassador Ahmet Bey. After the flag issue is solved, they deal with the uniforms; the wife of the ambassador sews the star and the crescent on their red uniforms. Selim Sırrı cannot be satisfied by making those athletes to pay out of their pocket and speaks to the journalist when he came back from Stockholm: “I almost cried. There wasn’t any Turkish athlete in the Olympics, while every other nation was represented.” It seems that he couldn’t have guessed that Vahram Papazyan will serve as a telegrapher for Ottoman army in Gallipoli Front.

Qrisian’s Question

The editor of Marmnamarz magazine Shavarsh Qrisian might have felt disturbed by this treatment, so he wrote an article that explains their loyalty to Ottoman Empire with examples of Armenians who contributed to the defense of the country in Balkans. He wrote: “The people who cheered for these athletes did so because they are from Ottoman Empire, not because they are Armenians. Why don’t you mention the names of these athletes from Ottoman Empire?”

Krisyan exiled to Ayash on 24 April 1915 with other Armenian intellectuals, before he received an answer to his question. The things he went through and saw on the road to Ayash were the living proofs that he had never been considered as an equal citizen of Ottoman Empire.

The “Armenian Sport and Gymnastics in the Ottoman Empire” exhibition in Yerevan caused internal questionings once again for many people with the feeling of resentment it created on the 100th anniversary of the genocide. During the last April, there were innumerable posters in Yerevan that read “I remember and I demand” in various languages. We remember and in fact, we never forget, that’s for sure, but what do we demand? A feeling of guilt in people’s hearts? Acceptance of genocide? Compensation? Land? Can all of these bring a whole civilization back that is already lost? The things we have lost are more than we can imagine…