Ter-Matevosyan: Armenians did not need KGB direction to understand what happened to them in 1915

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, in a speech to journalists on October 31, claimed that the enmity between Armenians, Azerbaijanis and Turks was fueled by Soviet-era propaganda and the KGB. Pashinyan stated, "When we say 'the Turk never changes,' they say the same thing about Armenians. When we say 'how can we trust Azerbaijan?' they say the same thing about Armenians. We need to free ourselves from the worldview shaped by KGB agents." Following Pashinyan's statement, Russian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zakharova noted that the KGB was "established in 1954, almost 40 years after the 1915 Armenian Genocide," characterizing the Prime Minister's words as "historically ignorant."

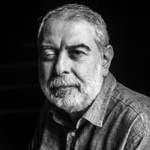

Professor Vahram Ter-Matevosyan of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the American University of Armenia, who has studied Russia-Turkey relations for many years, interpreted Pashinyan's words and Zakharova's response for Agos. Ter-Matevosyan, whose book has been translated into Turkish as "Kemalism Through the Eyes of Communism/Soviet Approaches to Turkey's Transformation," headed the Turkey Studies Department of the Institute of Oriental Studies at the Armenian National Academy of Sciences and specializes in the history and foreign relations and security policies of modern Turkey, as well as South Caucasus conflicts.RetryClaude can make mistakes. Please double-check responses.

Do Pashinyan's statements about the KGB and the Soviets reflect reality?

In his persistent effort to format deeply ingrained societal perceptions about Armenia and its neighbors, the Prime Minister of Armenia continues to make political statements that rely on sweeping generalizations, distortions, and outright misinformation. His grasp of Armenia’s political and social history over the past two centuries has repeatedly revealed a troubling mix of inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and contradictions. Dissecting every erroneous claim he made would require a lengthy historical analysis, but one point is beyond dispute: majority of his statements about history are profoundly ahistorical. When he speaks of the Soviet Union, which lasted for nearly seventy years, one is left wondering which period he even has in mind. Every decade of Soviet history bore its own distinct approach toward Turkey. The 1920s and 1930s, which marked the formative years of both states, demonstrate that the relationship was far from outright hostile. As I discuss in my monograph, the early Soviet Union had no geopolitical, ideological or political reasons, to cultivate anti-Turkish sentiments among Armenians.

So there was a consciousness that came from the lived horrific experience?

The generalizing claim he makes that Soviet propaganda shaped Armenian attitudes toward Turkey is not just simplistic, it is insulting to historical memory. The Armenians who survived the Genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire and the massacres inflicted by the Kemalist forces needed no KGB - which did not exist until 1954 - instruction to understand what had happened to their families, villages, towns, churches and sacred sites. Their perception of Turkey was not the product of Leninist-Marxist-Stalinist indoctrination but of lived horror and inherited trauma. In Soviet Armenia, the second largest city, Leninakan, was known as “Vorbaqakhak”—the “City of Orphans.” More than 30.000 children, whose parents had perished in the Ottoman Empire, grew up there and throughout their adult lives carried pain of unspeakable proportions. These were not products of propaganda; they were the living witnesses of extermination. Without the care of parents, they carried the memory of annihilation throughout their lives. To suggest that their understanding of Turkey was engineered by the Soviet state is a historical falsification and a moral affront.

We can't say the Soviets had no influence on Armenia-Turkey relations, can we? What kind of policies did the Soviets pursue on this matter?

Moving into the late 1930s and early 1950s, Soviet–Turkish relations entered a period of marked tension. Turkey’s gradual drift toward France and Britain, its close wartime cooperation with Nazi Germany, and its eventual accession to NATO created a deep geopolitical rift. The Soviet authorities, unsurprisingly, viewed Turkey with growing suspicion and occasionally flirted with the idea of mobilizing Armenians and Georgians to advance territorial claims. Yet these plans were poorly conceived and never progressed beyond diplomartic statements and vague discussions. The large-scale repatriation of 90.000 Armenians to Soviet Armenia between 1946 and 1949, who were survivors of the Genocide and lived scattered across Europe, the Middle East, and the United States, must also be understood in this geopolitical context. But some politicians today often fail to see the broader picture. Many Armenians who resettled in Soviet Armenia during the seven decades (aorund 170.000) brought with them powerful ideas of freedom, liberation, and justice, reigniting the public discourse about the lost homeland. Again, there was no need for Soviet propaganda or the KGB to cultivate anti-Turkish sentiment; lived memory and inherited trauma were far more potent.

With the onset of de-Stalinization, Khrushchev’s thaw, and the spread of dissident movements during trhe Brezhnev era, Armenians in the Soviet Union increasingly articulated their historical grievances and national aspirations on their own terms. As I have discussed elsewhere, the 1960s witnessed the revival of Armenian nationalism, nourished not by state manipulation but by a genuine societal impulse for historical truth and dignity.

To be sure, the Prime Minister is partly correct in acknowledging that the omnipresent Soviet censorship sought to restrain certain “excesses.” However, by the 1960s and 1980s, Moscow’s priority had shifted in the opposite direction—to suppress, not incite, national discourse. The genie was out of the bottle and the Soviet apparatus worked relentlessly to ensure that territorial and historical claims against Turkey and Azerbaijan did not escalate into public mobilization or intellectual rebellion.

I could continue this historical survey at length. But it suffices to underscore a simple truth: by grossly exaggerating the role of Soviet propaganda and the KGB in shaping Soviet Armenian national consciousness, today’s political leadership distorts history and undermines the authenticity of the Armenian people’s collective memory and belittles its agency. Previously, he also made similar claims about the role of Soviet propaganda about weaponization of the Armenian Genocide. The enduring narratives of loss, justice, and identity were not engineered in Moscow—they were born from lived experience, transmitted through generations, and carried in the hearts of those who survived. Armenia’s political leadership should remember that reshaping national memory requires intellectual integrity, not misguided revisionism. History cannot be rewritten to fit a short-term political agenda of one-sided reconciliation and peace-building, nor can trauma be erased with opportunistic rhetoric.