From Within a Mountain, Against It and Alongside It

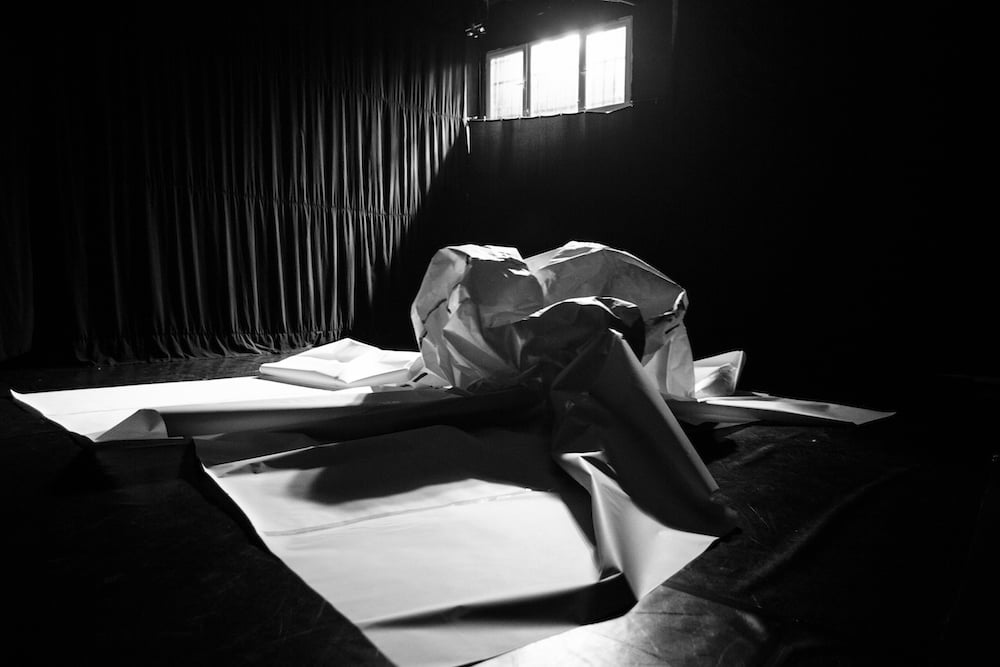

I finally had the opportunity to see Sar. It has been ten years since the work was first staged. Members of our collective, Araz Kojayan, Sesil Artuç, and Tamar Gürciyan, published an article in this column about this performance in October 2023. Over the years, Saro Usta and Mihran Tovmasyan have developed and transformed this performance; they themselves have changed and grown as the dramaturgy transformed them. At times they have become a mountain, at times garbage, at times seekers of ore within waste.

I was very late in seeing it;and yet it felt like a play I watch every day, a play I perform every day. As I watched, my entire life passed before my eyes. A story of destruction and self-erasure could hardly be told more powerfully.

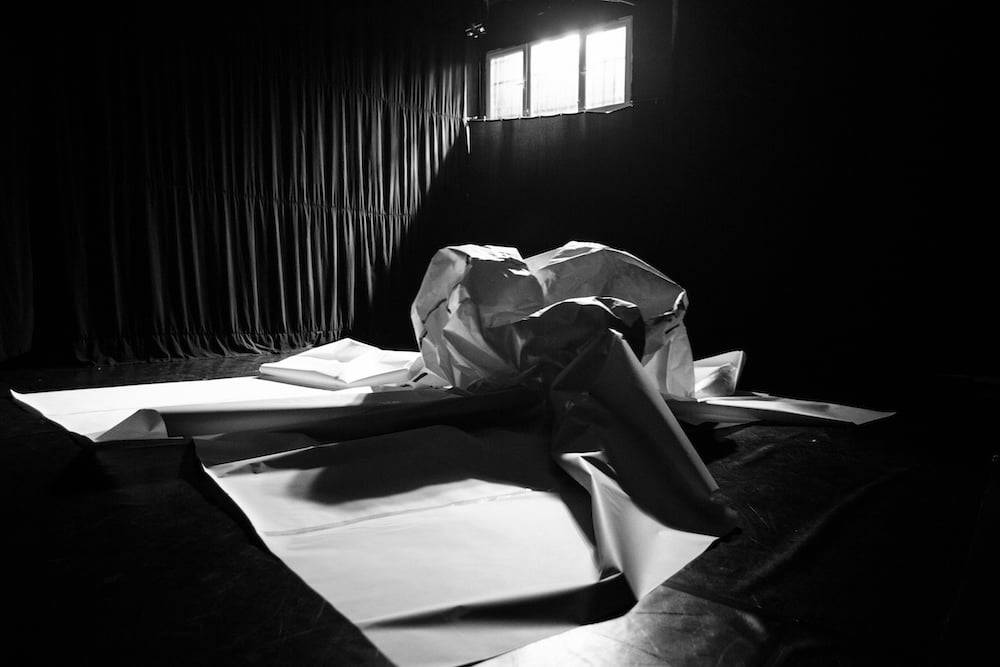

In the post-performance discussion, most of the questions from the audience focused on the material used in the piece. The primary material was paper. Paper represented both the mountain and the garbage. What material could better represent a people with such a rich history of writing and print culture than paper? With the exception of one or two people, most of those asking about the material dwelled on why paper was used, what kind of paper it was, the striking shapes and sounds it could produce, its monumental visual impact, and how it retained its power even when transformed into trash. Yet beneath these questions lay a deeper curiosity: what did this material actually represent? As spectators, we had understood what we wanted to understandbut what were the artists themselves trying to say? What, ultimately, was this struggle with paper, accompanied by extraordinary music for an hour, trying to convey?

What we first encounter as a majestic mountain, then as a heap of paper, and finally as trash, can also be read as opening the doors to a colonial world. Emerging from within a mountain, struggling against it, climbing to its summit, sitting on it, owning it;and the moment one owns it, turning it into waste.This can be read as a complete narrative of extraction.

In this sense, paper can represent both the colonized and the colonizer at once. The mentality that claims ownership of the mountain, turns it into garbage, and markets the fragments it extracts from that garbage as precious resources is a colonial, extraction-driven mindset. At the same time, the native who emerges from within the mountain,overwhelmed by its existence, the weight and terror of what it reminds, may turn into someone desperately trying to eliminate that massive presence, to destroy it, to turn it into trash. How many Armenian schools, how many Armenian families burned their own libraries, threw their books into wells, destroyed collections in heating boilers? How many Armenians felt a sense of relief in those moments, while simultaneously being engulfed by an overwhelming feeling of guilt? The inability to protect the values one has created is a historical legacy, which isoften entirely unrecognized.

Sar made me think of all this. But what it made me feel was even more important. For the first time in a long while, I emerged from a one-hour performance carrying a series of complex, intertwined emotions. In Europe, artistic works, such as novels, films, performancesthat address Armenians are largely didactic, constructed from within white supremacism, and saturated with epistemic violence. Feeling regret for having spent time on such works, or anger toward them, is almost inevitable. Sar, by contrast, made me feel how a people continues its struggle for existence despite the heavy burdens carried on its shoulders; how, even when forced to go on by constantly abandoning itself, denying itself, even turning itself into waste, it nonetheless sustains the hope that one day, in another time, another humanity might understand this struggleand be guided by it.