Ateş ‘Gâvur Mahallesi’ne de mi düştü?

Rahmetli anam “ateş düştüğü yeri yakar” derdi. Ateşin dini, dili rengi yoktur. Ateş bu kez Diyarbakır’da, Güneydoğu’da Kürt halkının yoğun olarak yaşadığı yerlere düştü. Gerekçesi ise yüzyıldır eksik olmayan ve bir türlü kapatılamayan ‘hendek’ler. Pek çok uzmana göre, bu ateş de bu hendekleri kapatamayacak. Bir zamanlar, Diyarbakır nüfusunun yarısına yakını Ermenilerden oluşuyordu. Bugün Diyarbakır’da yaşayan Ermenilerin sayısı ise iki elin parmaklarını geçmiyor. Ancak yüz yıl sonra her Pazar Müslümanlaşmış ya da Müslümanlaştırılmış Ermeniler, Surp Giragos Kilisesi’nin bahçesini doldurmaya başlamıştı. Ancak ateş ‘Gâvur Mahallesi’ne bir kez daha düştü.

Osmanlı döneminde Diyarbakır Vilayeti’nin tümünde Ermenilere ait 148 kilise ve 10 manastır bulunuyordu. Bu kiliselerden 11 adeti ise o dönemde kaza olan, günümüzdeki Diyarbakır ilinde yer alıyordu. Ermenilere ait olan görkemli ibadethanelerin bir kısmı camiye veya kışlaya dönüştürüldü. İçlerinden en belirgin ve ünlü olanı ise 1518’de camiye çevrilip, Kurşunlu Camii adını alan Surp Toros Kilisesidir. Bu kiliseye el konulmasının ardından 16. yüzyıl sonlarına doğru ise kilisenin mezarlığına Surp Giragos Kilisesi inşa edilir ve bölgenin Ermeni Başepiskoposluğu da buraya taşınır. Surp Giragos Kilisesi, 1881’de yanıp kül oldu. Bu yangın o tarihlerde Anadolu’nun pek çok yerinde destanlara konu oldu.

“Bin iki yüz doksan sekiz tarihinde

Khamiz Gecesi, Haziran sonunda

Mahi Racab, derler yirmi beşinde,

Şahri Amit’da oldu yangın. Yangın oldu dedilar küçük kilisede

Haklarından gelsun Hazreti İsa,

Yazık idi M’ambar Surp Giragos,

Yandı direkleri kalmadı suni.”

Kilise 1883’te Ermeni ileri gelenlerinin katkısıyla ikinci kez inşa edilir. Fakat Surp Giragos’un başından felaketler bu tarihten sonra da eksik olmadı. 1913’te yıldırım düşmesi sonucu çan kulesi yıkıldı. Yaklaşık iki yıl sonra anıtsal üslupla, yeni kule inşa edildi. Ancak tam da 1915 Ermeni Soykırımı arifesinde, kilisenin çan kulesi, yan taraftaki minareden daha yüksek olduğu gerekçesiyle top atışlarıyla yıkıldı. Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nda askeri karargâh, ardından Sümerbank’a ait depo olarak kullanıldı. Kilise 1960’lardan itibaren tekrar ibadete açıldı ancak 1980’lere doğru Ermenilerin can güvenliklerinin yeniden tehlikeye girmesiyle birlikte son büyük göç de başladı. Surp Giragos da bu süreçte adım adım harabeye döndü. Ancak İstanbul ve dünyanın dört bir yanına dağılmış Diyarbakırlı Ermeniler, Surp Giragos Kilisesi’ni 2011’de tekrar ibadete açtı. Kilisenin içinde yer aldığı Sur ilçesinin savaştan ne kadar etkilendiği ise ilçeye giriş çıkışların başlamasıyla birlikte aydınlanacak.

Surp Sarkis Kilisesi

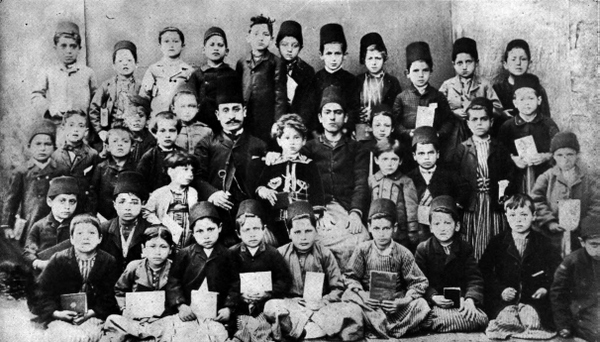

Diyarbakır ‘Gâvur Mahallesi’nde yer alan ikinci kilise ise Surp Sarkis idi. Surp Giragos’un 1903’te 480 erkek, 274 kız olmak üzere toplam 754 öğrenci, 20 öğretmen, Surp Sarkis’in ise 80 erkek, 50 kız olmak üzere 130 öğrenci, 5 öğretmene sahip birer okulları vardı. Bu iki okul Ermeni siyasi partilerinin çekişmelerine bağlı olarak kendi aralarında zaman zaman tatlı, zaman zaman da oldukça sertleşen bir rekabet yaşadı. Kız öğrenci sayısının yüksekliği dikkat çekicidir. 1892’de Surp Giragos’a bağlanan ruhani önderlik sekreterliğini de yapan Nacaryan’a ait bir başka okul da yer almaktaydı.Diyarbakır’da ayrıca Protestan ve Katolik Ermenilere ait okullar da vardı. Ermenilerin bir kısmı bu okullarda eğitim görmekteydi.

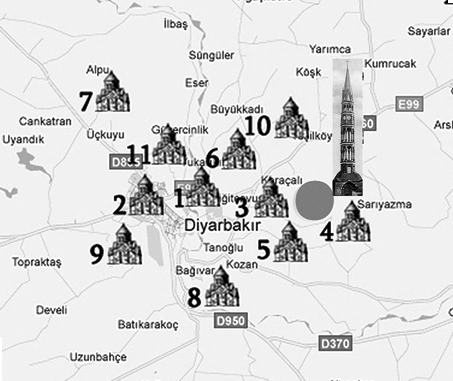

Diyarbakır merkezde 1. Merkez: Surp Giragos 2. Merkez: Surp Sarkis 3. Alipınar: Meryem Ana Manastırı 4. Bahçecik: Surp Taniyel 5. Çirnik (Pınardüzü): Meryem Ana 6. Karabaş: Surp Simon 7. Karakilise (Dökmetaş): Ermeni Kilisesi 8. Kabi/Keyabi (Bağıvar): Surp Krisdofor 9. Keterbi/Kıtırbil: Surp Hagop 10. Satıköy: Surp Tukhmanug 11. Zemieğik (Elidolu): Surp Yeğya kiliseleri yer almaktaydı. Bu kiliselerin önemli bir kısmı kamu kuruluşlarınca farklı amaçlarla kullanılıyor. Pek çok Ermeninin ilk eğitimlerini aldıkları Süleyman Nazif İlkokulu’nun bir bölümü bu kiliselerden birine aittir. Diyarbakır’da farklı mezheplerin ve farklı etnik toplulukların kiliseleri iç içe yer alıyorlardı. Örneğin, Surp Giragos’un yan sokağında Mar Petyun Keldani Kilisesi yer alıyordu.

Eğitim seferberliği

1847’de İstanbul’da kurulan Antsnıver Hayuyats Ingerutyun’un (Fedakâr Ermeni Kadınlar Derneği) bir şubesi de Diyarbakır’da kuruldu. Amacı Pazar günleri özellikle kızlara Ermenice okuma yazma öğretmekti. Bu dernekten ayrı olarak zanaatkârlara Ermenice okuma, yazma öğretmeyi amaçlayan ‘Hayrenasirats’ ve ‘Mesropyan’ adlı iki dernek daha kuruldu. İlki 1865’te Kudüs’ten yeni dönen ve aldığı eğitimi, edindiği bilgileri halkının yararı için kullanmak isteyen Tovmas Zarzavatçıyan tarafından kuruldu. Zarzavatçıyan, ‘Hayrenasirats’ aracılığıyla Surp Sarkis Kilisesi sınırları içinde bir okul kurarak yeni metodlarla Ermenice dersler vermeye başladı. Hayrenasirats Kurulu üyeleri ki Surp Giragos Kilisesi semtinde oturuyorlardı, çocuklarını eğitim görmek için yarım saatlik uzaklıktaki bu okula gönderiyorlardı. Küçük çocuklar, tüm olağanüstü hava koşullarına rağmen Pazar dersleri için bu okula gidiyorlardı. Zarzavatçıyan, zamanla Pazar derslerini yetişkinler için de vermeye başladı. Yetişkinleri farklı sektörlerde yeni metodlarla üretim yapmaya teşvik etti. Bunun ilk sonucu, dilenmek ya da kiliseden geçinmek yerine meslek öğrenme ve ilerleme isteğinin toplumsallaşması oldu. Pek çok zanaatkâr da mesleklerinde önemli ilerlemeler kaydetti.

Diyarbakır’da Ermenice harfli Türkçe olarak yayımlanan, bir süre de Ermenice, Türkçe ve Arapça olmak üzere üç dilli olarak yayımlanan, ‘Diyarbakır’ adlı bir vilayet gazetesi de yayımlandı. Resmi genelgelerin, kanunların ve ticari ilanların yer aldığı bu gazete, haftada 1000 adeti Türkçe, 500 adet ise Ermenice olarak basıldı.

Kamulaştırmanın geçmişi

Tartışmalara ve tepkilere konu olan kamulaştırma 1983 tarihli Kamulaştırma Kanunu’un 27. maddesine dayanarak, Bakanlar Kurulu kararı ile yapıldı. Valilik, “Bu karar, bölgedeki tüm özel mülklerin kamulaştırılması anlamına gelmemektedir” şeklinde bir açıklama yapsa da yapılan kamulaştırma Sur’daki tüm kiliselerin bu kamulaştırmanın kapsamına girdiği gerçeğini değiştirmiyor. Ayrıca Surp Giragos Kilisesi’ne ait Suriçi’ndeki dükkan ve ev gibi mülkler de kamulaştırılmış oldu.

Kamulaştırma Kanunu’nun teknik ayrıntılarına girmeden, Suriçi’ndeki kamulaştımaya ışık tutan yasanın 27. maddesini okuyalım:

“3634 sayılı Milli Müdafaa Mükellefiyeti Kanununun uygulanmasında yurt savunması ihtiyacına veya aceleliğine Bakanlar Kurulunca karar alınacak hallerde veya özel kanunlarla öngörülen olağanüstü durumlarda gerekli olan taşınmaz malların kamulaştırılmasında kıymet takdiri dışındaki işlemler ....”

Bu madde akıllara ‘Milli Müdafaa Mükellefiyeti Kanunu nedir?’ sorusunu getiriyor. 1939 tarihli kanunun ilgili maddeleri de şöyle:

Madde 1: Seferberlik ve savaş hali ile bu hallerin henüz ilan edilmemiş olduğu ancak savaşı gerektirebilecek bir durumun meydana geldiği gerginlik ve kriz dönemlerinde yapılacak seferberlik hazırlıkları ile kıtaların toplanması esnasında, alelade vasıtalarla temin edilemeyen bütün askeri ihtiyaçları veya hizmetleri bu Kanun hükümleri dairesinde vermeye veya yapmaya her şahıs borçludur.

Madde 2: Bu mükellefiyetlerin Türk topraklarının tamamı veya bir kısmı üzerinde yapılmasına başlanacağı zamanı İcra Vekilleri Heyeti tayin eder.

Yasanın bu maddeleri vahim bir duruma işaret ediyor. Devlet Suriçi’nde yaşananların bir savaş olduğunu kabul etmiş oluyor. Bu savaş hali tabirinin, Ermenilerin hafızasındaki yeri hiç iyi değil elbette. İster istemez 100 yıl öncesine gidiyorum.1915 Ermeni Soykırımı öncesinde de Diyarbakır sokaklarında esen dostluk rüzgarları bir anda İttihat Terakki cellatlarınca yok edildi. Diyarbakır’da bir sabah vakti Ermeni tüccarlar, doktorlar, avukatlar, mühendisler, dükkan sahipleri, devlet memurları, hâkimler, rahipler hapsedildi, ağır işkencelerden geçirildi. Silah arama bahanesiyle başlayan huruç hareketi bir katliama dönüştü. Askere alma gerekçesiyle toplanan Ermeni gençleri kitlesel olarak yok edildi. Şehir nüfusunun yarısına yakınını oluşturan Ermenilerin geri kalanlarının çöle doğru yolculukları başladı. Diyarbakır ekonomisi de o tarihte çökmeye başladı. Kuyumcular, taş ustaları, bakır tüccarları, pamuk, ipek, tahıl, yün ve benzeri malların ticaretiyle uğraşan Ermenilere Süryaniler, Keldaniler, Katolik ve Protestan Ermeniler, Yezidiler, Rumlar ve az sayıda da olsa Yahudiler eklenince Diyarbakır renklerini kaybetti.

Kentsel dönüşüm

İTÜ Mimarlık Fakültesi’nde öğrenci olduğum dönemde, depremler ve yeni yerleşimler dersimizde Varto örneği verilirdi. Deprem sonrası Vartolulara yeni konutlar yapılmış, ancak onlar bu evlerin ihtiyaçlarına cevap vermediği gerekçesiyle kendileri için daha uygun olduğuna karar verdikleri mağaraları barınak edinmişlerdi. Anadolu’nun pek çok yerinde deprem konutları adında viraneye dönüşmüş yerler var. Depremlerde ilk yıkılan binaların kamu yapıları olduğu akıllardan çıkmış değil. İstanbul’da Romanların yaşadığı Sulukule’de sözde dönüşüm projesi hazırlanmış, ancak yapılan konutların kamu bürokrasisine peşkeş çekildiği ortaya çıkmıştı. Beyoğlu Tarlabaşı’nda da sınırdışı edilen Rum ve Ermenilere ait tarihi mülklere dönüşüm adı altında neler yapıldığını her gün seyrediyoruz.

Ülkemizde hükümetlerin, yerel yönetimlerin kentsel dönüşüm adına gerçekleştirdikleri, tüm iyi niyetli söylemlere rağmen bir rant ekonomisi olmaktan ileri gidemedi. Kentsel dokular, sivil mimarlık örnekleri yok edildi. Suriçi’nin o dar sokakları dikkate alınmadan yapılacak ‘dönüşüm’le Suriçi’nin tarihi dokusundan geriye hiçbir şey kalmayacaktır. Suriçi arazileri mülkiyet açısından da problemler yaratacak, “bu arsalar size ait değil, zaten işgalciydiniz” gerekçesiyle orada yaşayanlar hak mahrumiyetine uğrayacaklar.

Toprak İşgalleri Komisyonu

Bu mülkiyet tartışmaları ister istemez bizi 110 yıl öncesine de götürüyor, çünkü Diyarbakır bu açıdan çok önemli bir merkez ve ilginç bir tarihi var. Anadolu’da Ermenilerin can ve mal güvenliğiyle ilgili sorunları hiç eksik olmadı. 1860 Berlin Konferansı’nda Ermenilerin can ve mal güvenliğini sağlayacağına söz veren Osmanlı devleti tam aksini yaptı. Ermeni kırımları birbirini izlerken, 1895-1896 arasında pek çok vilayette Ermenilere ait topraklar, tarlalar, evler, bağlar, bostanlar, değirmenler zorla işgal edildi. Bu işgallerin boyutu Ermenilere ait kilise, manastır ve mezarlıklarına kadar uzandı. Yerel başvurulardan bir sonuç alamayan, mahkeme kararlarının da uygulanmadığını gören binlerce Ermeni, sorunlarını doğrudan İstanbul Ermeni Patrikhanesi’ne iletti. Patrikhane Cismani Meclisi Dr. Nazaret Dağavaryan başkanlığında Toprak İşgalleri Komisyonu adında bir kurul oluşturdu. Bu komisyon, Patrikhane’ye gelen tüm şikayet ve belgeleri inceleyerek bir rapor hazırlayıp, Cismani Meclise sundu. Cismani Meclis, bu raporu 1911’de Patrikhane’nin resmi yayını olarak, komisyon üyelerinden Keğam Der Garabedyan ise kendi raporunu ayrıca yayınladı. Yayınlanan raporlarda gaspların gerekçeleri kategorize edilip, büyüklükleri, o günkü değerleri, kimler tarafından işgal edildiği tek tek belirtildi.

Gaspçılar arasında Kürtler, Türkler, Çerkeslerin yanı sıra devletin çeşitli kademelerinde yer alan yetkililer de bulunuyordu. Ağırlıklı olarak Kürt beyleri ve aşiret reislerinin, yer yer de sivil halktan kişilerin bu gasplara katıldığı bu raporlardan anlaşılıyor. Devletin işgal ettiği arazilerin çoğuna göçmenler yerleştirilirken yer yer de bu mülkleri yıkarak devlet binası yapıldığı da görülüyor.

Diyarbakır vilayeti sınırları içinde yer alan kimi yerleşimler günümüzde vilayet sınırları dışında kaldı. Diyarbakır Vilayeti’nde de pek çok işgal gerçekleşti. Kasaba ve köylerde yaşayan, toprakları gasp edilen Ermeniler önce merkezlere, oradan da iş ve aş için İstanbul gibi şehirlere ve nihayetinde Avrupa ve Amerika’ya göç etti. Yer yer de Suriye, İran ve Kafkaslar’a göç ettiler.

Toprak İşgalleri Komisyonu Raporu’nda, Diyarbakır Vilayetinde gerçekleşen gasplardan bazılarını şunlar:

Diyarbakır, Ergani: Şu anda harabe olan Surp Nışan Manastırı Mahmut oğlu Kasım tarafından zorla işgal edilmiştir.

Diyarbakır, Palu: 640 lira değerindeki,160 dönüm toprağı ile birlikte Tilküz Surp Haç Manastırı 1895’te Şerif Bey tarafından zorla işgal edilmiştir. İtiraz ve şikayet edilmiş ancak sonuçsuz kalmıştır.

Diyarbakır, Derun: [Gökbaşı mah. Kocaköy]: Köylü Haço Aroyan’a ait 160 dönümlük tarla, 1896’da Hacı Raşit tarafından zorla işgal edilmiştir.

Diyarbakır, Lice, Çomayek [Okur köyü, Hani]: Mardiros Ğazaryan’ın 2 bağı 1896’da Mahmut Asat ve Ali Bekir tarafından zorla işgal edilmiştir.

Diyarbakır, Piran köyü [Atalar köy - Çüngüş ]: Tovmas Boğosyan’ın 150 lira değerindeki şahsi bir evi, bir dükkanı, bir bostansi Zıki Ağanın oğlu Hacı tarafından zorla işgal edilmiştir. (Açıklama: dükkan 200 kuruş karşılığı)

Diyarbakır, Farkin [Silvan]: Üç şahsa ait 2 arazi, bir değirmen ve bostan Abdullah Beyzade sadık ve Maran Bey tarafından zorla işgal edilmiştir.

Diyarbakır, Silvan, Terbidi [Terbile Kırmatepe köy - Çermik]: Köylü Khaço Şahyan ve başkalarının 160 dönüm 11 tarlası 1895’te Abdullah Bey tarafından zorla işgal edilmiştir.

Diyarbakır, Silvan, Hacigan köyü [ Karacalar]: Ohan Usoyan’ın toprakları 1896’da Kürtler tarafından işgal edilmiştir.

Diyarbakır: Avaneg [Sulak ] köyü Ermenilerinin toprakları Kürtler tarafından işgal edilmiştir.

Diyarbakır, Lice, Karazig: 11 Köylüye ait 7 dönüm 6 bağ, bir mera ve 8 tarla 1895’te isimleri genel listede yer alan Kürt zalimler tarafından zorla işgal edilmiştir.

Diyarbakır, Argni [Ergani], Dazan: Köyün Ermenilerine ait üç tarla Fatah bini Kalo tarafından işgal edilmiştir.

Diyarbakır, Siirt, Garzan (Yanarsu): Merida köyünden 6 şahsın yaklaşık 100000 kuruş değerindeki toprakları Reşitan Aşiretinden Tamo Ağa Bini Nay zorbası tarafından zorla işgal edilmiştir.

Surların başına gelen

Diyarbakır’ın surları da çok tehlike atlattı. Tarihi Dikran Arşaruni Krallığı’na kadar uzanan surlar Bizans ve Osmanlı dönemlerinde de giderek gelişti ve büyüdü. 1930’lara gelindiğinde şehrin boğucu sıcaklığının tek nedeni sözde hava akımını engelleyen bu surlar olarak görülmeye başlandı. Surlar, yer yer çok miktarda dinamitler konularak yıktırılmaya başlandı. Şehir halkı, surları sökerek kendi inşaatlarında kullanmaya teşvik edildi. 1932’de bölgede bulunan arkeolog Prof. Albert –Louis Gabriel’in girişimleri sayesinde büyük bir felaket önlendi ve surların yıkımı durduruldu.

Diyarbakır surları aynı zamanda zindanlarıyla da ünlüdür. Osmanlı coğrafyasının farklı yerlerinden gelen mahkûmlar bu zindanlarda kalmışlar. Örneğin, Bulgaristan’ın pek çok şehrinde Osmanlı döneminde Diyarbakır zindanlarında çürüyen Bulgar aydınlarına ait heykel ve tablolara rastlayabilirsiniz.