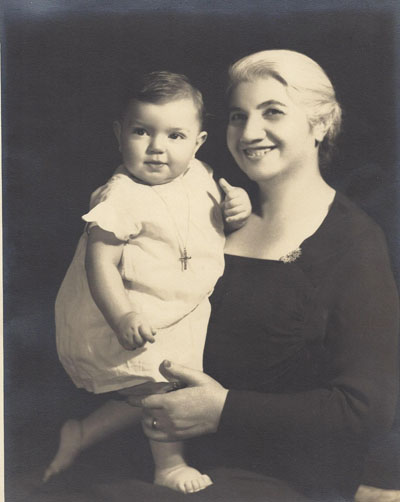

Ağustos 2015’te, dedem Hampartzum ve anneannem Elmas Tutuian’ın tanıştığı, evliliklerinin 11 yılını geçirdikleri, çocukları Arsenik, Aşot ve annem Bercuhi’yi dünyaya getirdikleri şehir olan Kastamonu’yu ziyaret ettim.

Anneannem Elmas’ın dediğine göre, dedem orduya alınana kadar - ki kendisini bir daha görmemişler - Kastamonu’da çok huzurlu ve mutlu bir hayatları varmış. Dedemin ardından anneannem, yengem ve çocukları da evlerini ter etmeye zorlanmışlar ve kağnı üzerinde anneannemin ismini bilmediği bir yere götürülmüşler. Anneannemin “ağalar” olarak anlattığı iki erkek kardeşin evinde tek göz bir odada hep birlikte kalmaya başlamışlar.

Daha sonra jandarmalar anneannemin sekiz yaşındaki oğlu Aşot’u almışlar, “Türkleştirmek” üzere. Anneannem, diğer iki çocuğu Arsenik ve Bercuhi’yi yengesine bırakarak, jandarmaların Aşot’u götürdüklerini söyledikleri Daday’a ulaşmak için dağlar boyunca yürümeye başlamış. Onu bulduğunda, onun için geri geleceğine söz vererek bir polis komiserinin yardımını almak üzere Kastamonu’ya yürümüş. Dedem Hampartzum’un arkadaşı olan bu komiser, daha öncesinde anneannemi korkunç şeylerin olacağı ve Müslüman olması gerektiği konusunda uyarmış bir memurmuş. O dönemde bunu reddeden anneannem, bu sefer Aşot’u ve ailesini Kastamonu’ya geri getirmek için din değiştirmeyi kabul etmiş. Anneannem benimle bu hikâyeyi paylaştığında ben genç bir ergen olarak çaresizce 1950’lerin Amerika’sının kültürüyle kaynaşmaya çalıştığım, onun tektipleştiren temsillerinden farklılaşmamaya özen gösterdiğim bir dönemdeydim.

Anneannemin Ermeni soykırımının bir kurbanı ve kurtulanı olduğuna dair hiçbir fikrim yoktu o zaman. Soykırım ya da diğer travmatik olaylardan kurtulan diğer ailelerin aksine, benim ailem, ne 1915 öncesi ne de sonrasında Türkiye’deki deneyimleri hakkında hiç konuşmazdı. Eski ülkeden ve orayı ziyaret etme niyetinden bahseden kimse olmadı ailede. Ta ki anneannem 1969’da, 82 yaşındayken, dört ay kalmak üzere İstanbul’a gidene kadar.

Zamanını bekleyen hikâye

Anneannemin hikâyesi on yıllarca bilincimin arkasında saklı kaldı. 1970’lerin sonunda, yeni yeni gelişmekte olan kadın çalışmalarından ve bu alanın kadın hikâyelerine yaptığı vurgudan çok etkilenmiş olarak anneannemin hikâyesini bir kez daha dinlemek istedim. Aynı zamanda bu dönemde, soykırım mirasına sahip bir Amerikalı Ermeni olmanın politik duruşumu nasıl şekillendirdiğini, toplumsal cinsiyetin inşasında ırk/etnisite ve sınıfın oynadığı role yaptığım vurguları nasıl güçlendirdiğini fark etmeye başlamıştım. Kendimi hem politik hem duygusal olarak anlamak için anneannemin hikâyesine ve hayatımdaki etkisine daha derinden bakmam gerekiyordu.

Anneannem, teyzem ve annemle 1915 deneyimleri üzerine gerçekleştirdiğimiz görüşmeler çok güçlüydü, ancak Kastamonu’daki hayatları hakkında çok az şey öğrenebilmiştim. Ne Kastamonu’yu, ne de Türkiye’nin herhangi bir yerini, ziyaret etmek ise aklımın ucundan geçmiyordu.

Türkiye’ye ilk adım

2009 yılında, Hrant Dink Anısına Atölye Çalışmaları kapsamında ‘Osmanlı Topraklarında Toplumsal Cinsiyet, Etnisite ve Ulus-Devlet’ üzerine konuşmam için bir davet aldım. İlk başta davet e-postasını silmeye çok yaklaşmışken, sonunda katılmaya karar verdim. O zaman Kastamonu’nun nerede olduğunu ve İstanbul’a ne kadar uzak olduğunu merak ettim ama asla ziyaret etmeyi düşünmedim. Ailemin verdiği onca kayıp ve çektiği onca ızdırabın ardından orayı ziyaret etmeyi aklımın ucundan bile geçirmedim - ki İstanbul’da olmak bile beni yeterince zorlayacaktı.

Konferans akıllara durgunluk vericiydi. Sadece soykırım üzerine değil, politik olarak benim de durduğum yerden toplumsal cinsiyet, ırk/etnisite, sınıf ve cinsellik üzerine çalışan onca insanla tanışmak beni şaşkına çevirdi. O zamandan beri aynı zamanda hem çok tanıdık ve hem çok korkutucu olan bu topraklara birçok kez geri geldim. Ancak Kastamonu’ya gitmeye karar vermem ancak Türkiye’ye yedi kez geldikten sonra, partnerim Martha ve sevgili arkadaşım Ayşe Gül’ün beni güçlü bir şekilde teşvik etmesiyle gerçekleşecekti. Hep beraber gidecek ve bir gece kalacaktık.

Kararımı verdikten sonra bile seçimim konusunda emin değildim. Annemin doğum yeri olan ama hakkında neredeyse hiçbir şey bilmediğim şehre gitmenin anlamı neydi? Ailemin hikayesini bölük pörçük biliyordum. Elmas’ın iki yaşındayken annesini kaybettiğini, aileden bir başkasıyla evli olan ablası Turfanda’nın babalarını genç Elmas’ı yanlarına vermesi için ikna ettiğini ve Sivas’ta yaşayan Donigyan’ların Elmas 17 yaşına girmeden bir süre önce Kastamonu’ya taşındıklarını biliyordum.

Bir fotoğrafın anlattığı

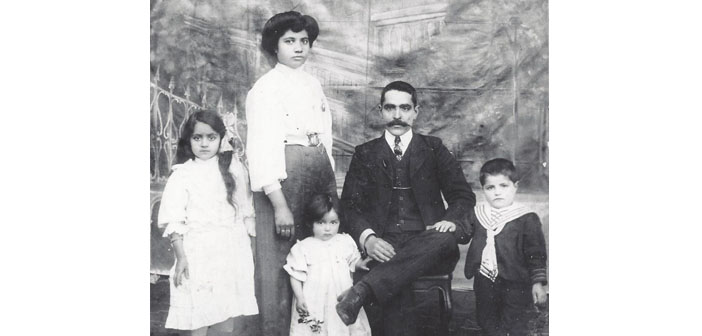

Anneannem Kastamonu’da evlenmişti: Turfanda’nın kocası Arakel'in arkadaşı ve komşusu Hampartzum Tutuian ile. Dedem hakkında çok az bilgiye sahip olmama rağmen anneannemin saklamayı başardığı bir aile fotoğrafından nasıl göründüğünü biliyordum. 1915 öncesinde çekilmiş bu fotoğrafta, sandalyeye oturmuş çok yakışıklı Hampartzum’un sağında Elmas, iki yanında ise küçük oğlu Aşot ve en küçük çocuk olan Bercuhi duruyor, en büyük çocukları Arsenik ise Elmas’ın sağ tarafında duruyor.

Fotoğraf dışarıdan başka bir şey görünmesin diye boyalı bir arka planın önünde çekilmiş ama ben hala kendimi bu yüz yıldan eski fotoğrafa bakarken, hayatlarına dair bir şey görebilme umudu taşırken buluyorum. Dedemle ilgili bildiğim şeyler ise, Hampartzum’un dokumacılık işi yaptığı; ailenin bahçeli büyük bir evde yaşadığı, ve anneannemin çamaşır, temizlik ve yemek için yardımcılara sahip olduğu.

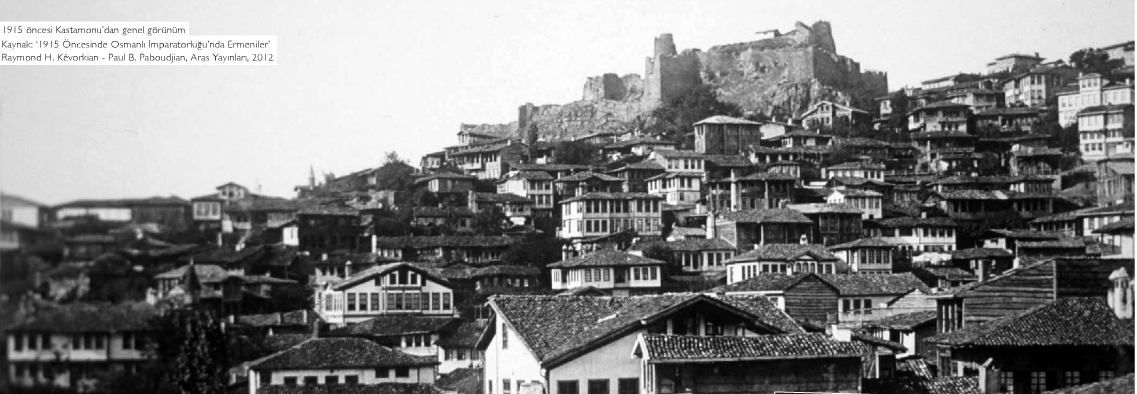

Teyzem ve amcam Ermeni okuluna gitmişler gerçi ama yaşadıkları yerde yalnızca Ermeniler yokmuş. 1915’te Kastamonu’daki Ermenilerin ya öldürüldüğünü ya da evlerinden zorla çıkarıldığını varsaymıştım ama kesin bir bilgim yoktu - ta ki 1914 öncesinde Kastamonu’da 10000 Ermeni’nin yaşadığı ve hayatta kalan birkaçının Meskene, Der Zor ve Abuharar’a ulaştığını Raymond Kevorkian’ın yakın zamanda paylaştığı sarsıcı araştırmasını okuyana kadar.

Neyi hatırlamak neyi unutmak

Travmatik tarihler genelde hafıza mekânlarının duygusal etkisini arttırırlar ama ben ailemin Kastamonu’daki hayatıyla ilgili o kadar az bilgiye sahiptim ki esas kaygım orada olmanın bana ya hiçbir şey hissettirmemesi, ya da kendimi hissetmem beklenen duyguların içinde biraz yapay olarak bulmaktı. Bütün bu duygularla Kastamonu’ya doğru yola çıkmak üzere uçağa bindim. Bir sonraki 24 saat boyunca hissettiklerim ise bir dizi anlık ışık çakması gibiydi – gelişleri gibi kayboluşları da ani olan güçlü duygusal parlamalar. Ailemin orada olmuş olduğu, o sokaklarda yürümüş, o çarşılarda ticaret yapmış, o dükkânlarda alışveriş yapmış olduğu gerçeğini bedenimde hissettiren anlık çakmalar.

İlk çakmayı uçak alçalırken yaşadım. Dışarıya baktığımda gördüğüm sarp dağlar, anneannemin 30 küsur yıl önce yaptığımız görüşmelerdeki sesini getirdi bana. Ashot’u almak için yürüdüğü Daday yollarında yaşadıklarını anlattığı Ermenice kelimeleri duydum; “O dağlarda yalnızım, beni duyuyor musun? Karanlık. Yol yok. Hiçbir şey yok. Yalnızım. Anlıyor musun?” O dağları görünce, anneannemi onların üzerinde yürürken hissettim; korkmuş ama oğlunu geri almak için kararlı. Sonra uçak indi ve Kastamonu’ya geldiğimiz anonsu yapıldı. Küçük terminale doğru yürümeye başladığımda anneannemin varlığı gitmişti.

İçinden geçen bir nehir ve etrafını çevreleyen tepeleri olan bu güzel küçük şehrin sokaklarında yürümeye başladık. Tahmin edilebileceği gibi çok az kişi İngilizce konuşabiliyordu ve iletişimimiz Ayşe Gül aracılığıyla oluyordu.

Ayşe Gül, otel çalışanlarından Kastamonu’nun tekstil ürünleriyle tanındığını ve ürünlerin satıldığı sokakları öğrenmişti. Üzerinde büyük siyah desenlerin olduğu krem rengi kumaştan masa örtüleri, halı ve önlüklerin vitrinlerde sergilendiği bir caddeye geldik. Daha önce hiç böyle şeyler görmemiştim ve bir masa örtüsünün ucunu tuttuğumda, teyzemin bana babasının kumaşa baskı yapmak için bir makine icat ettiğini anlattığını hatırladım ve bir ürperme hissettim. Hampartzum hakkında bildiğim çok az sayıda şeyi teyzemden öğrenmiştim.

Anneannem ara sıra dedemden bahsederdi, ama yorumları hep aynıydı – dünyadaki en mükemmel ve zeki adam oydu. Sürekli bunu tekrarlardı. Ama şimdi Kastamonu’nun taş baskı dokumalarıyla çevriliyken, bu desenlerin onun tasarladığı makineyle basılıp basılmadığını merak ediyordum. Kastamonu’nun bu özel tekstil ürünleriyle tanınmasını o sağlamış olabilir miydi? Kendimiz ve arkadaşlarımız için masa örtüsü aldık ve ben Hampartzum Tutuian’a küçük bir bağ hissederek oradan ayrıldım.

Sıktığım o el

Öğle yemeği için yediğimiz lezzetli pastırmalı pidenin ardından – anneannem hiçbir zaman içine pastırma koymamış olsa da buna “etli ekmek” derdi – arkeoloji müzesine gittik. Müzenin bekçisi oldukça ilginç koleksiyon hakkında sahip olduğu zengin bilgisini, özellikle üzerinde kadın figürü bulunan eserlere odaklanarak gururla paylaşıyordu ama Ayşe Gül ona neden Ermeniler hakkında bir şey olmadığını sorduğunda, Kastamonu’da Ermenilerin olmadığını söyledi. Şu anda şehirde yaşadığını bildiği sadece iki Ermeni vardı: bilinen en iyi araba tamircisi ve “mükemmel bir insan” olan bir ayakkabıcı.

Ayşe Gül ona 1915’te anneannemin burada yaşadığını söyledi ve bekçi hiç tereddütsüz elimi sıkmak istedi. O kocaman eliyle ellerimi kavradı ve gözlerimin içine baktı. Bekçinin, şehrinde yaşamış olan 10.000 Ermeni’nin ölümünden ve hayatlarının bu şehirden silinmiş olmasından bihaber olması, ailemin, insanlarımın burada yok edilmiş olmaları karşısında hissettiğim kızgınlık ve acıyı bir nebze de olsa hafifletiyordu. Bir Ermeni ile kişisel bir ilişkisi olmamışsa, Anadolu’daki pek çok insan gibi onun da Ermenilerin aslında bu köylerde, kasabalarda veya şehirlerde yaşamamış olduklarına dair varsayımı sorgulamak için bir sebebi olmamıştı belki de.

Devlet dairesi korkusu

Bir sonraki durağımız bir devlet dairesiydi. Ayşe Gül Kastamonu’yu ziyaret etmem için beni ikna etmeye çalışırken, nüfus müdürlüğünden ailemle ilgili daha fazla bilgiye ulaşabileceğimiz ihtimalinden de bahsetmişti. Elmas Tutuian’ın anneannem olduğunu kanıtlayan belgelerle zırhlı olarak, otomatik silahlı nöbetçiler tarafından korunan büyük Nüfus Müdürlüğü binasına doğru yaklaştığımda, Türkiye devletinin temsilleriyle ilk karşılaştığımda – örneğin, kocaman bayraklar, ilk geldiğim yılda İstiklal Caddesi’ndeki polisler karşısında – yaşadığım korku geri gelmişti.

Türkiye devletinin resmi memurlarından Ermeni ailemle ilgili bilgi vermelerini isteyecektim. Mideme bir ağrı girdi ve olabildiğince hızlı bir şekilde koşarak oradan kaçmak istedim, ama Martha ve Ayşe Gül ile sarmalanmış olarak basamaklardan yukarı çıktım.

Bilgisayarlı bir masada oturan bir adama yönlendirildik ve karşısına oturduk. Ayşe Gül ailem hakkında sorular sormaya başladı, Arlene Avakian ve Elmas Tutuian dediğini duyduğumda, getirdiğim belgeleri sıkıca tutan ellerimin yapış yapış ve soğuk olduğunu fark ettim. Adam Ayşe Gül’e Nüfus Müdürlüğünde 1940’lardan önceye dair hiçbir belge olmadığını söylerken bana döndü ve gözlerime baktı. Tüm belgeler Ankara’ya taşınmıştı. Oradaki genel müdürlüğe giderek sormamızı ya da Amerika’da konsolosluktan bilgi talep etmemizi salık verdi. Sıktığım ellerimi tekrar açtım ve ben de ona gülümsedim.

Akşamın sonunda otele geri döndük ve anneannemle 1979’da yaptığım görüşme kaydından Kastamonu’dan Daday’a yürüyüşünden bahsettiği kısmı bulduk. Anneannemin eski bir Kastamonu evi olan otel odasında yankılanan sesi, tüm kaygılarıma rağmen çıkabildiğim bu anlamlı yolculuğa güçlü bir son nokta oldu.

Şimdi gitmek ve keşfetmek istiyorum

Ama Kastamonu’da olmak, sokaklarında yürümek, sadece küçük parçalar. O fotoğraftaki pozu verdikleri zamanlarda anneannem ve dedemin hayatlarının nasıl olduğunu, yani hayatları paramparça olmadan önce nasıl yaşadıklarını muhtemelen asla tam olarak bilemeyeceğim. Hampartzum’un nasıl öldüğünü asla bilemeyeceğim. Ailemin neden ölene dek yürütülmediğini, neden at arabası ile taşındıklarını ve neden bir eve yerleştirilip beslendiklerini asla bilemeyeceğim. Amcamın Türkler tarafından ne kadar süre tutulduğunu, o sırada neler yaşadığını ve bu deneyimin hayatını nasıl etkilediğini asla bilemeyeceğim. Anneannem gittiğinde annem ve teyzeme ne olduğunu, travmatik bir zamandaki bu ayrılığın onların hayatını nasıl şekillendirdiğini asla bilemeyeceğim. Ama onların yuvası, memleketi olmuş olan şehri az da olsa deneyimledim ve ışık çakması gibi yaşadığım o anların üzerimdeki etkileri hâlâ devam ediyor…

Yıllar boyunca Kastamonu’yu ziyaret etmek konusunda tereddütte olan ben, şimdi tekrar gitmek istiyorum ve bu sefer Ermenilerin yaşamış olabilecekleri, kiliselerinin, okullarının bulunduğu yerleri keşfetmek istiyorum. Ailesi Kastamonu’da yaşamış diğer Ermenileri bulmak ve parçalarımızı birleştirmek istiyorum. Belki de bu şekilde Kastamonu’da Ermenilerden kalan boşluğu biraz olsun doldurabiliriz.

(Çeviri: Dilara Çalışkan)

Eğer Kastamonuluysanız ve bir başka Kastamonuluyla ilişkiye geçmek isterseniz lütfen [email protected] adresinden Arlene Avakian’a yazın. Türkçe iletişim için [email protected] adresinden Ayşe Gül Altınay’a ulaşabilirsiniz.

Bir dilim pastırmanın hatrı

Kastamonu’nun en eski ve en iyi sucuk ve pastırma yapan dükkânından arkadaşlarımız için hediyeler almak üzere öğlen yemeği yediğimiz yere geri döndük. Oraya vardığımızda pastırmayı kesen tek kişi olan dükkân sahibi camiye gitmişti.

Açıkçası orada olmadığı için sevinmiştim. Gün zaten yeterince duygusal geçmişti ve sakinleşmek için bir bardak votkaya ihtiyacım vardı. Ayşe Gül, şehrin eski kısmında bulunan Kurşunlu Han Otel’de alkol bulunma olasılığının çok yüksek olduğunu söyleyerek oraya gitmeyi önerdi. Meydanda yürürken, sandaletlerimin ince tabanından eski kaldırım taşlarını hissettim. Elmas ve Hampartzum’un ayakları da büyük ihtimalle bu taşlar üzerinde yürümüştü.

Teyzem, amcam ve annem, Elmas ve Hampartzum’un ellerini tutarken büyük ihtimalle küçük çocukların o sallanan adımlarından atmışlardı. Onların 1915 öncesi hayatlarını biraz olsun anlayabilmek için bu hisse tutunmak istedim, ama Kurşunlu Han’a vardığımızda bu his buharlaşmıştı. Akşamüstü güneşinin vurduğu büyük avlunun güzelliği beni biraz sakinleştirdi. Garson hanın tarihinin 15. yüzyıla dayandığını, ilk zamanlarda tüccarların, seyyahların kaldığı canlı bir yer olduğunu, 19. yüzyıldaysa dokuma, tekstil ve diğer ürünlerin satıldığı bir çarşıya döndüğünü söyledi. Dokuma ürünlerinin alınıp satıldığı bir çarşı. Hampartzum da büyük ihtimalle bu handa bulunmuş, burada ticaret yapmıştı. O avluda oturuyor olmamız ne inanılmaz bir tesadüftü! Ama saat altıyı geçmişti ve kapanmadan pastırmacı dükkanına gitmeliydik.

Küçük dükkâna döndüğümüzde genç adamın geri gelmiş olduğunu gördük. Siparişimizi aldı ve pastırmaları kâğıt inceliğinde kesmeye başladı. Ayşe Gül, adamın arkasındaki duvarda duran fotoğraflardaki erkekleri sordu, o da babası, dedesi ve büyük dedesi olduğunu söyledi. 1870’de kurulmuş olan bu dükkânı dört nesildir ailesi işletiyordu. Dükkân açıldıktan 30 yıl sonra da Elmas, Kastamonu’da genç bir gelin olarak yaşamaya başlayacaktı.

Ayşe Gül, genç adama dedelerinin 1915’te burada yaşamış bir Ermeni olan anneanneme büyük ihtimalle pastırma satmış olabileceğini söyledi. Müzedeki nöbetçi ve nüfus müdürlüğündeki memur gibi, hiç tereddüt etmeden yüzüme bakarak gülümsedi ve bir dilim pastırma verdi. Çok lezzetliydi – belki de bugüne kadar yediklerimin en iyisi…