Balakian: Şiddetin yankıları geçmişten bugüne ulaşıyor

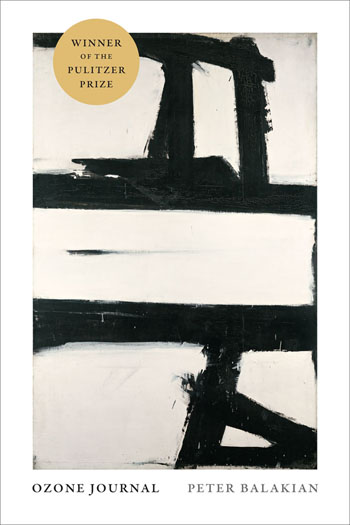

2016 yılı şiir dalında Pulitzer Ödülü, ‘Ozon Günlüğü’ kitabıyla Amerikalı Ermeni yazar, akademisyen ve şair Peter Balakian’a layık görüldü. Türkiyeli okurun daha çok edebiyat dışı eserleriyle, özellikle de Ermeni Soykırımı’yla ilgili yazılarıyla tanıdığı Balakian, Amerika’nın en prestijli ödülü olarak kabul edilen Pulitzer Ödülü’nü alarak şiir dünyasının en önemli isimlerinden biri haline geldi. Pulitzer Ödülü böylelikle 1940’da William Saroyan’dan sonra ikinci defa bir Ermeni’ye verilmiş oldu.

65 yaşındaki Balakian, halen New York’taki Colgate Üniversitesi’nde sosyal bilimler fakültesinde ders veriyor. Pulitzer Ödüllü Balakian’la edebiyattan siyasete, geniş bir yelpazede konuştuk.

Agos okurları sizi daha çok edebiyat dışı eserlerinizle, özellikle de soykırım üzerine yazılarınızla tanıyor, daha önce de bu konularda fikir alışverişinde bulunmuştuk. Son olarak da Avrupa İnsan Hakları Mahkemesi’nde görülen Perinçek-İsviçre Davası’yla ilgili görüşlerinize gazetede yer vermiştik. Okurlarımıza şair tarafınızdan bahsedebilir misiniz?

Geçmişte farklı konularda pek çok düzyazı metin kaleme almış olsam da, yazar olarak hayatımın merkezinde hep şiir vardı. Şiir yazmaya 1970’lerin başında henüz üniversite yıllarımdayken başladım, ilk şiir kitabım ‘Baba Balıkgözü’ (Father Fisheye) 1980’de yayımlandı. Pulitzer Ödülü’ne layık görülen ‘Ozon Günlükleri’ (Ozone Journal) ise yedinci şiir kitabım oldu.

Bir şair olarak, lirik şiirin daha açık ve kapsayıcı bir formunu yaratmakla ilgilendim, bu da beni ‘yatay yazım’ diye adlandırdığım kavrama doğru yönlendirdi. Bu kavramla ilgili daha önce ‘Mengene ve Gölge’ (Vise and Shadow) başlıklı deneme kitabımda bir yazı yazmıştım.

Lirik şiirin daha açık bir formu dediğimde asıl ilgilendiğim şey, genelde pek çok farklı bölüm ve kesitten meydana gelen uzun şiirler oluyor. Görünüşte bağlantısız olup fark edilmeyen güçlerin ördüğü ağlarla birbirine bağlanan gerçeklikler üzerinden, yaşanan deneyimlere dair bir karmaşa ortaya çıkıyor. Edebiyatta her zaman işlerin doğasını, insanların serüvenini anlamaya çalışan bir karakter olur. Bahsettiğim bu daha açık formla birlikte, kendi edebiyat türümde, siyasi ve sosyal gerçekliklerle çatışıyorum. Bunlar, iklim değişikliği, soykırım, AIDS, terörizm, travmatik hafıza, kişisel ve aracılı gerçeklik, aşk, ölüm, sanat ve kültür gibi konular olabilir.

İlk şiirlerinizde de 1915’in izlerini görebiliyoruz…

1970’lerin sonunda tarih ve travmatik hafızayla ilgili şiirler yazmaya başladım, bunlar Ermeni Soykırımı’yla ilgiliydi. Bu şiirlerle büyükannemin 1915’te Diyarbakır’daki ölüm yürüyüşünden ve tüm ailesinin katledilişinden bir şey çıkarmayı umdum. Ailede bu katliamdan sadece o ve iki küçük bebeği kurtulmuştu. Bu şiirler onun bu travmatik akıbetinden ve hafızasından parçalar yakalamanın yollarını ve tabii bu akıbetin şimdiki zamanı etkileyen müzmin yöntemlerini arıyordu. Lirik şiirin, travmatik geçmiş ve sonrasında yaşanan hayata yeni boyutlar ekleyerek, onlara cevaplar üretip dönüştürebileceği düşüncesini pek çok açıdan hissetmiştim. Bu minvalde ‘Ermenistan’ın Tarihi’ (The History of Armenia), ‘Nenem Çorba Yapıyor’ (Granny Making Soup), ‘Halep Yolu’ (The Road to Aleppo), ‘Büyükannem Geri Geliyor Diye’ (For My Grandmother Coming Back) gibi şiirler 70’lerin sonuna doğru Amerika’daki edebiyat dergilerde çıkmaya başladı ve 1983’te çıkan ikinci kitabım ‘Işığın Hüzünlü Günleri’nde (Sad Days of Light) yer aldı.

Pulitzer Jürisi’nin sizin için kullandığı ifadelere ne dersiniz? Jüri sizin şiiriniz için “Küresel bir tehlike ve belirsizlik çağını destekleyen, eskinin kayıplarına ve trajedilerine tanıklık ediyor” demişti. Sizce jüri ödülü neden size verdi?

Ödül jürileri, bir kazanan seçiyor çünkü ellerine aldıkları o kitaptaki edebi işin şekline değer veriyorlar. Bu sizin ortaya koyduğunuz dil ve formla ilgili. Şiirimin daha büyük bir arenada kabul gördüğünü görmekten çok mutlu oldum.

Ödülü alan ‘Ozon Günlüğü’ kitabınızdan da bahsedebilir misiniz biraz?

Yeni kitabımın merkezinde ‘Ozon Günlüğü’ diye yine uzun bir şiir var, bir önceki kitabım ‘Ziggurat’taki ‘Tren/Zigurat/Mersiye’ (A-Train/Ziggurat/Elegy) adlı uzun şiirin devamı niteliğinde… ‘Ozon Günlüğü’ elli beş bölümlük bir şiir, Suriye çöllerinde Ermeni Soykırımı’ndan kurtulanlardan kalanları araştıran bir karakterle başlıyor ve bu durum o karakterin 1980’ler New York’unda yaşadığı yoğun anıları canlandırıyor, AIDS virüsü ve iklim değişikliği ise bu karakterin kişisel meselelerle mücadelesi için bir bağlam kuruyor. Karakterin bir anlam arayışında koyulduğu yol, onu büyük bir caz ve blues yapımcısı ile gireceği diyaloğa sürüklüyor. İkilinin Miles Davis üzerine yaptıkları tartışma ilham verici, buradaki kurgusal yapımcı karakteriyse George Avakian ismi üzerine kurulu…

Kitaptaki diğer şiirler kriz bölgeleri, sınır ülkelerinin karmaşıklığı ve diaspora kimliği gibi konuların yanı sıra, aşk, kayıplar ve sanat gibi kişisel gerçeklikleri de ele alıyor. Bazı şiirler New Mexico’nun Amerikan yerlisi köylerini ya da Nairobi’nin varoşlarını veya Gümrü ile Ani arasındaki boşlukta Türk-Ermeni sınırını keşfe çıkıyor. Fakat şiir her zaman dille ve kişinin her hangi verili bir gerçekliği tekil bir tür edebi ahenkle keşfedişidir ki, şairin alameti ve yaşam nefesi budur.

Sizinle birlikte bu sene Pulitzer Ödülü’ne layık görülen diğer kişilere baktığımızda, hepsinin mülteci krizi, tutsak işçiler, IŞİD tehdidi gibi meseleleri ele aldığını görüyoruz. Bugünün dünyasında pek çok kötülük var, bir yandan da geçmişten bugüne aktarılanlar var. Sizin de şiirlerinizde güncel olayları uzak geçmişte yaşananlara bağlamayı sevdiğinizi görüyoruz. Bu açıdan Ermeni Soykırımı ve bugün yaşanan trajediler sizi nasıl etkiliyor? Yirminci yüzyılın ilk soykırımının yaşandığı Ortadoğu’da bugün başka trajediler yaşanıyor, bunun hakkında ne dersiniz?

Orta Doğu karmaşık bir kültürel-siyasi çeşitlilik ve kriz ortamı olmaya devam ediyor. Burası zengin bir medeniyet kaynağı ve bu gerçek, aynı zamanda bugünkü yoğunluğu ve yaşanan sorunları körüklüyor. Orta Doğu yüzyıllar boyu sömürgeci boyunduruk ve demokrasiden yoksunlukla şekillendi. Unutmamalıyız ki, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu da sömürgeci bir hareketti. Hıristiyanları, Arapları, Kürtleri ve Ortadoğu’nun pek çok diğer kültürünü sömürdü.

Yirminci yüzyılın başlarında Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’ndaki Ermenilere, Süryanilere ve Rumlara yapılan soykırımın yanında, Araplar ve Kürtlerin kitlesel bir şekilde yerinden edilmesi gibi pek çok insanlığa karşı suç işlendi. Birinci Dünya Savaşı’ndan sonraki sınırlar Fransızlar ve Britanyalılar tarafından çizildi, onlarsa bölgenin kültürel karmaşıklığına duyarsızdı. Bu durum o zamandan beri bölgedeki istikrarsızlığı körükledi.

Kitlesel şiddet ve kültürel yıkımın yankıları, yirminci yüzyılın başından yirmi birinci yüzyılın başına ulaşıyor. Fakat farklılıklar da var. Örneğin IŞİD hareketi ile 1915 Türkiye’sindeki İttihatçılar arasında fark var. Ama Orta Doğu’daki Hıristiyan kültürünün hali istikrarlı bir şekilde yok olma eğiliminde. Hepsi Osmanlı Türkiye’sinin Hıristiyan toplumlarına ve kültürüne yönelik taarruzuyla başladı, bu 1819’da Sakız Adası’nda Rumlara yapılan katliama kadar gidip Levant Bölgesi’nde, Anadolu’da ve Küçük Asya’da on dokuzuncu ve yirminci yüzyıllar boyunca Hıristiyanlara yönelik baskı ve zulümle devam eder. Bugün de Mısır’daki Kıptileri ve Irak ve Suriye’deki Hıristiyanları görüyoruz, hepsi saldırı ve taarruz altında. Bu büyük bir insan hakları trajedisi ve uluslararası toplumun bu konuyla ilgilenmesi gerekiyor.

William Saroyan’dan sonra Pulitzer Ödülü’nü alan ikinci Ermeni edebiyatçısınız. Saroyan hakkında neler söylemek istersiniz?

1940’ta ödülü kazanan William Saroyan’ın izinden gitmek bir onurdur. Saroyan, Amerikan edebiyatında ve Ermeni uluslar ötesi edebiyatında biricik bir figürdür. 1930’daki eseriyle Ermeni kültürünü edebiyat haritasına yerleştirip Amerikan ve dünya edebiyatına yaratıcı katkılarda bulundu, özellikle de 1930’lar ve 40’larda lirik kısa hikâyeleri esneterek kurduğu kendine has türüyle… Eserleri her zaman okunmalıdır.

Balakian’ın Pulitzer Ödüllü kitabı ‘Ozon Günlüğü’nden bir şiir

Here and Now

The day comes in strips of yellow glass over trees.

When I tell you the day is a poem

I’m only talking to you and only the sky is listening.

The sky is listening; the sky is as hopeful

as I am walking into the pomegranate seeds

of the wind that whips up the seawall.

If you want the poem to take on everything,

walk into a hackberry tree,

then walk out beyond the seawall.

I’m not far from a room where Van Gogh

was a patient — his head on a pillow hearing

the mistral careen off the seawall,

hearing the fauvist leaves pelt

the sarcophagi. Here and now

the air of the tepidarium kissed my jaw

and pigeons ghosting in the blue loved me

for a second, before the wind

broke branches and guttered into the river.

What questions can I ask you?

How will the sky answer the wind?

The dawn isn’t heartbreaking.

The world isn’t full of love.

Burada ve Şimdi

Gün ağacın üzerinde sırça sarı şeritlerle geliyor.

Size günün bir şiir olduğunu söylediğimde

Yalnızca size konuşuyorum ve beni sadece gökyüzü dinliyor.

Gökyüzü dinliyor; gökyüzü

ben dalgakıranı kamçılayan rüzgârın

nar tanelerine doğru yürürkenki gibi umutlu.

Şayet şiirin her şeyle boy ölçüşmesini istersen

bir çitlembik ağacının arasına gir

ve sonra dalgakıranın ötesinden çık.

Van Gogh’un hasta oturduğu odadan fazla uzakta değilim – başı yastıkta dalgakıranda

yalpalanan karayeli dinliyorfovist yaprakların lahite teğet geçişini

işitiyor. Burada ve şimditepideryumun havası yanağımdan öptü ve rüzgâr

dal budağı kırıp oluktan nehre akıtmadan önce

hüzünde gölgelenen güvercinler beni bir anlık sevdi.

Sana hangi soruları sorabilirim?

Gökyüzü rüzgâra nasıl yanıt verecek?

Gündoğumu kalp kırıcı değil.

Dünya sevgi dolu değil.