Asia and Africa collection of British Library in London offers books that tell a story of Kurdish language and culture that is not widely known. More than hundred works in Kurdish, especially children's books, that were published in Soviet Armenia in Cyrillic, Armenian and Latin alphabets have come to light again thanks to cataloging efforts of Michael Erdman, library's curator of Turkish and Turkic languages.

A poetry compilation involving both Kurdish folk tales like ‘Şêrê Çevqul’ (Greedy Lion) and milestones of socialist movement, stories like 'Heft Rreng' (Seven Colors) in which a bear and a monkey try to deceive a wolf and terms like rhyme and prosody are explained, works written in order to expand Kurdish vocabulary as well as to explain Soviet ideology to children... A small Kurdish collection involving such works are available in British Library. Publishing his works on Kurdish books on the website of British Library on April 24, Michael Erdman reveals the transformation of Kurdish in Caucasus from '20s to the present. Kurdish children's books that were published in Soviet Armenia and brought to light again by Michael Erdman are valuable for understanding this culture that went through many ruptures in terms of language, politics, society and economy.

Erdman says, “Although numerically small, the publishing history of Armenia’s Kurds highlights the importance of education as an agent of reproduction of both national culture and language, and State-sponsored ideologies. While the Kurds of Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran faced severe restrictions on the use and propagation of their native language, those living in the Soviet Union were able to transform fully their mother tongue into a literary standard. In spite of this, the Socialist, anti-nationalist content of the materials produced kept the core of the struggle for cultural and political self-determination far to the south of Armenia, paving the way for these publications to become relics of a parochial, historically bounded arena of Kurdish cultural production.”

Though small groups of Kurdish people live in many places of Caucasus today, Kurds, constituting 2% of Armenia population today, are historically the most crowded minority group in the country... Majority of the society on this land speaks Kurmanji, the dominant Kurdish dialect in Turkey, Iraq and Syria; however, Soviet policy, which acknowledged the existence of a distinct Kurdish nation contrary to assimilation policies of many countries, enabled cultural and social development of Kurdish society and thus of its language.

Saying, “Nevertheless, Kurds faced the same ups and downs of nationality policies that affected many of the other national minorities in the USSR”, Erdman explains this transformation in Kurdish by arrangement and rearrangement of language system in Soviet Union during '20s, '30s and '40s. Kurdish society began to express itself with Armenian letters in '20s and then used Cyrillic and Latin letters in accordance with the changed Soviet policies.

First of all, what was the motivation for conducting such a work? What was the initial idea and will you continue this work?

I started workings at the British Library in 2015. At that time, I was cataloging the Ottoman, Turkish and other Turkic language books and periodicals. I found many Kurdish books published in Soviet Armenia and I thought them to be very rare and interesting material. I researched the usage of Kurdish in Armenia, and I understood that these books were telling the story of a little-known ethno-linguistic group. I wanted to share these materials with other individuals interested in Kurdish, Kurdology, Armenia or Kurdish-Armenian relations, and so I decided to write this work.

Do the works in Kurdish that we saw in your article belong to British Library? Can you talk about Soviet-era Kurdish works that the library contains?

During the Soviet period, the British Museum (within which the Library found itself prior to 1973) and then the British Library regularly bought books from Soviet libraries or publication concerns, and sometimes it would sign exchange agreements with these libraries. In this way, every year we would receive ten or twenty books in Kurdish from them and we would send books in English to them in return. In the past, during the period before e-commerce, such agreements were common, because it was very difficult to purchase books from Soviet countries. Today, the British Library has more than one hundred Kurdish books published in Armenia. Many of them are school books or literary anthologies, but some are linguistic, ethnographic or historical studies. They tell us about the social life and history of Kurdish groups living in Armenia, and also paint a picture of Kurds’ adherence to the Soviet system.

You say that there is a difference between Kurdish in Soviet region and Kurdish in Turkey, Syria and Iraq due to the structure of Soviet Union. Can you explain this? What is the reason for this difference?

The Kurds of the Caucasus use one of the dialects of Kurmanji. Their dialect is close to Turkish Kurmanji, but there are some differences in phonology and grammar. For example, the ezafe construction is created with the use of ‘a’, but in Turkish Kurmanji it is formed with ‘ê’ and in Iraqi Sorani ‘î’ plays this role. Of course, in Soviet Armenia, both Russian and Armenia were the most widely spoken languages and both were official. As such, new terms were usually taken from these two languages. In Turkey, Kurds use Turkish word; Iraqi or Syrian Kurds, on the other hand, borrow new terms from Arabic; and in Iran they take new words from Persian. The same process is seen in western and eastern Armenian: the one takes new words from Turkish, French or Arabic, while the other takes them from Russian or Persian.

Different alphabets are used in the books. Why is that? Is there any specific reason for using Armenian alphabet or others?

Standardized written languages are a product of the nation-state era. Until the 19th century, religious communities would use their sacred alphabets and, in the East, the state did not enter into the language question. As such, given than the majority of Kurds are Muslims, they often wrote in Arabic letters. However, there is a tradition of Kurdish materials written in Armenian letters, and the British Library holds four or five examples of this. I believe that these holy books were published for Kurdish-speaking Armenian Christians, because the Kurmanji in these texts is close to Turkish Kurmanji. After the First World War, at the start of the nation-state era, every nation-state wanted to standardize its official and national language. In Turkey, this process continued until 1928. In this year, Atatürk created the Latin alphabet. For Kurds, because they did not their own independent state, the state apparatus did not try to create a unitary orthography. In 1933, Celadet Bedirhan created the Latin alphabet for Kurmanji and later Said Kaban Sedqi formed Sorani on the basis of the Persian alphabet; but neither Bedirhan’s nor Sedqi’s became official. In Armenia, the alphabet created in Tiflis by Akob Kazaryan and based on the Armenian one was used in the 1920s, but it does not appear to have been made official. It was not very popular and in 1929 it was replaced with a new alphabet. This writing system was the “Uniform Alphabet”: with a few changes, it was the same one that was used for Turkic and other languages and dialects of the region. The “Uniform Alphabet” was a Latin one and it was used until the end of the 1930s. The Soviet government announced that it would be used officially for these languages. However, at the end of the 1930s, the Stalinist government did not wish to encourage easy communication between the minorities of the Soviet Union and communities living beyond its borders, and thus a new writing system was created for Kurdish and other languages and dialects. This writing system took the Cyrillic one as its basis, and it was used until the 1990s. Some Turkic republics still use it, but it has disappeared from Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and the Kurdish communities of Armenia.

What do the books you mentioned tell?

These books are generally composed of stories, short stories or poetry. They were written for children and young adult. Sometimes they are love or historic poems, while others are poems about Soviet heroes, Soviet history or Marxist-Leninist ideology. The short stories are taken from traditional Kurdish tales and altered. The editor generally simplified the texts and sometimes rewrote the contents in order to reflect communist ideas.

You talk about especially one writer, Emine Evdal. Can you talk about her story? Why are this writer's works important? For instance, you talk about her work titled “Şerê Davit” and state that content of this work tells many things about Kurdish language's journey in Soviet era.

Emine Evdal was born in 1906 in the vilayet of Kars in modern Turkey. His family were Yezidis and, between 1914 and 1918, he lost his father, mother and brother. After the First World War, he migrated to the Caucasus and there studied at a Worker’s School in Tblisi. He became a teacher and taught in Yezidi villages. In 1931 he began his studies of Kurdology at Yerevan University and finished his doctorate in 1944. At the same time, he worked as a journalist for Soviet Armenia’s only Kurdish newspaper, Rya Taza. After finishing his doctorate, he became a researcher in the Kurdology Section of the Soviet Armenian Academy of Sciences. In 1959 he became the head of the Academy’s Oriental Language Division. Throughout his life, he published more than fifteen books. Some were works of poetry or fiction, while others were linguistic guides and studies. He died in Armenia in 1964.

In your work, you compare Kurds lived in Soviet region and Kurdis living in Turkey, Syria and Iraq in terms of cultural production and make an observation about the social structure of Kurds in Soviets. Can you explain this further?

In the Soviet Union, every official minority had the right to mother tongue education and cultural development. This, of course, we only theoretical, but in Soviet Armenia, Kurds were able to educate their children in Kurdish and to develop modern Kurdish literature and linguistics thanks to this idea. As such, both the language and the culture survived and advanced. At the same time, Kurdish language and culture were either neglected or prohibited because of nationalist and cultural assimilationist policies in Turkey, Syria, Iran and Iraq. Apart from a short period in Iraq in the 1970s, Kurdish publications and education in these countries was very basic and impoverished because of this. The Kurds of Armenia were a minority within a minority (Armenians were a minority within the Soviet Union, and Kurds made up less than 2% of Armenia’s population), and their political organization was very week. But their cultural life existed in a much freer and stable form than that of Middle Eastern communities.

Today, Kurds are citizens of an independent Armenia, and they participate in its political, economic and cultural life. They no longer use the Cyrillic alphabet, and in its place they write according to the Latin orthography. A Kurdish newspaper by the name of Azadiya Wellat (Freedom of the Fatherland) is published in Armenia, and thanks to financial support from the Armenian government, Rya Taza, the newspaper at which Emine Evdal wrote, is once again published. While historical grievances between Kurds and Armenians remain, Armenia’s Kurds’ situation is stable and they continue to publish newspapers, magazines and books in their mother tongue.

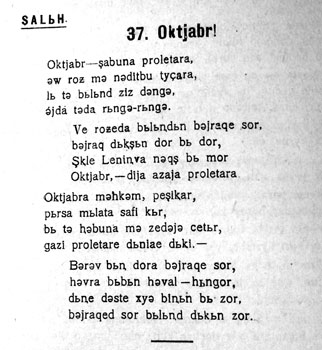

“Қteba Zmane Kyrmançi” and “Oktjabr” October Revolution with Kurdish folk tales

"In the early 1920s, Armenian letters were first used for Kurdish, although this was abandoned in favour of the Latin alphabet in 1927. Among the Kurdish titles from Armenia held by the British Library, Қteba Zmane Kyrmançi, a reader for native Kurdish-speaking 4th year students from 1933, shows us the second stage of this journey. The work is written in a modified Latin script similar to those employed for Turkic languages within the Soviet Union during the same period. The idea was to create a uniform representative of the phonemics – the underlying sounds – of each of the languages to which it was applied. There is therefore no attempt at harmonizing this Latin-script Kurmanji with similar dialects further south in Turkey or Syria. This is understandable, given that the goal of Soviet linguists and central planners was not linguistic unification, but rather socio-economic unification leading to the creation of one, unitary Soviet nation.

This is even more evident when we look at the content of the readers, rather than their form. Although the reader dates from the first five years of Stalin’s reign, it already shows the hallmarks of the “National in form, Socialist in content” ethos of Stalinist nationalities management. Poems about October (an allusion to the October Revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power) mingle with illustrated folk tales and traditional stories. Children are entertained with pictures of warriors, bandits and princes in traditional Kurdish garb while also reminded that “Oktjabr – şabuna proletara” (October is the rebirth of the proletariat), and that “Bǝjraqed sor bьlьnd dьkьn zor” (Many will raise red flags). The 1933 reader is clear proof that the codification and standardization of a language – albeit within the confines of the Soviet state – could be used to serve a cause other than nationalism.”

“H’k’yated Jimaeta K’urdî”

During the 1960s, the task of compiling readers for a new generation of Kurdish-language students fell to Hajie Jndi, one of Soviet Armenia’s most prolific Kurdish authors. His H’k’yated Jimaeta K’urdî contains a wealth of Kurdish folktales, short stories, poems and the like, all rendered in proper Cyrillic Kurdish. They are sanitized of any suspect ideological components, and occasionally illustrated to bring home a particular point. These collections, by a man who is believed to have authored some 110 books, articles, studies and other written works, demonstrate the central role played by Kurdish folk culture in identity-formation processes for Kurdish communities, even in the nominally post-national Soviet Union.

“Şerê Davit” Kurmanji with Latin and Cyrillic letters

The author of this particular reader, Eminê Evdal, evidently survived the ravages of the Great Purge and the Second World War, and continued writing in Kurdish – this time in the Cyrillic alphabet – in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. The Library holds a number of his poetry collections, including Memê û Zinê, the name of one of the stories in the 1933 reader, and P’êrişan, as well as other readers for the fourth year of classes at Kurdish schools in Soviet Armenia. In the 1957 edition, the poem Oktjabr is no longer present. In its stead is Lenin, written by C. Genco. It is a panegyric to the father of the Soviet Union, complete with sketched portrait. Evdal’s poem Şerê Davit did survive the decades, and thanks to the copy held by the British Library, we can compare the 1933 and 1957 versions, picking out the orthographic, syntactic and semantic deletions and additions, while also marveling at the sheer visual differences between the Latin and Cyrillic renderings of Kurmanji.

“Gezgezk” and “Heft Reng”

Part of the process of countering overly nationalistic content was the heavy reliance on ideological and class-conscious elements within the compositions. Other items held by the Library show the extent to which Marxist-Leninist ideas were woven into children’s stories and poems. In the anthology entitled Gezgezk (Nettle), personified animals on the cover clue us into the allegorical nature of these poems and stories. We see a monkey and a bear dragging off a wolf – an animal that Soviet children would soon become acquainted with as an underhanded cheater, thanks to the cartoon Nu, Pogodi!, which first aired in 1969. Gezgezk contains simple poems that introduce children to meter, rhyme, prosody and an expanded vocabulary of the Kurdish language, while also indoctrinating them with State-sponsored ideology. Animals and villagers were indeed favourite means of doing this, as we can see in another anthology of children’s poetry held by the Library, Şêrê Çevqul (The Greedy Lion). This collection includes works such as Ker û Ga (Ass and Cow), and Padşa û Gundi (King and Village), both of which harken to the rural imagination generally contained in Kurdish folktales and other oral literature, while also hammering home core components of the Socialist struggle.