Australia, New Zealand and Turkey: A 'special' relationship

JAMES ROBINS

Over the last few years, our understanding of the Armenian Genocide and the violent founding of the Turkish Republic has become much deeper and broader. Thanks to Taner Akçam, we have a complex picture of how power was wielded by the Ittihad. Ryan Gingeras and Uğur Üngör, among others, have analysed the precise details of destruction in specific places like the Sea of Marmara and Diyarbakır. Avedis Hadjian has written movingly of Turkey’s ‘hidden Armenians’ – the children and grandchildren of assimilated or forcibly converted Christians.

Research has also expanded to different nations and their connections to the story of the Genocide, nations that don’t usually appear in the traditional histories. Australia and New Zealand are notable examples of this growing field of research, which was kickstarted by Vicken Babkenian in his 2016 book Armenia, Australia, and the Great War.

We now know, for example, that the invasion at Çanakkale on April 25th 1915 – Anzac Day – was the final ‘trigger’ in the Ittihad’s decision for annihilation. Later, dozens of Anzac troops held as Prisoners of War by the Ottomans witnessed that annihilation: the killing fields, death marches, and concentration camps. They either recorded what they saw in their diaries, or published accounts in books and newspapers once they returned home. For example, the Australian lieutenant Leslie Luscombe wrote about the “sad and depressing sight” in Eskişehir of “a considerable number of Armenian women and children…huddled together” waiting to be piled into railcars on their way to “some distant concentration camp.” In the Taurus Mountains, the New Zealander Edward Opotiki Mousley saw “a great crowd of Armenian and Greek peasants with old men and old grey-haired women and children carrying small bundles or articles of cooking, all herded together en route for somewhere…In this way they are moved from place to place, their number dwindling until all have gone.”

Some Australians and New Zealanders can even lay claim to being rescuers or liberators. Gallipoli veterans Stanley Savige and Robert Nicol were part of a small volunteer force that helped to defend at least 60,000 Armenians and Assyrians who were fleeing annihilation in Urmia in 1918. Robert Nicol sacrificed his life in doing so.

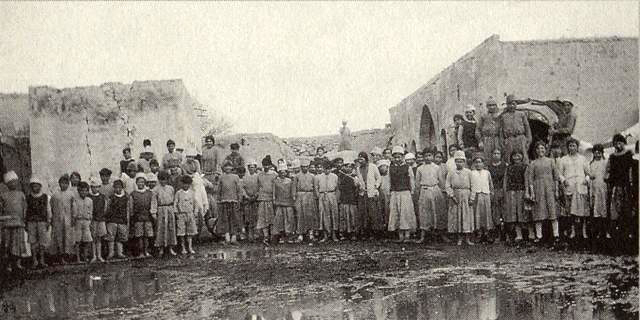

There were tens of thousands of articles and op-eds detailing the Genocide printed in New Zealand and Australian newspapers throughout 1914-1918, and these two nations also formed a crucial link in the “golden chain of mercy” set up by Near East Relief as part of the international humanitarian efforts to aid survivors of the Genocide. There were large relief drives throughout the 1920s, and thousands of ordinary people donated money and supplies. Some even travelled to the zone of genocide to help, like John and Lydia Knudsen from Christchurch who ran the ‘Australasian Orphanage’ at Antelias, Lebanon. (The orphanage buildings were later sold and became the seat of the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia).

On the surface, these details form a tiny part of the wider story of the Genocide, and are not altogether unique. A larger number of British soldiers were witnesses to the deportations. Russian troops have a greater claim to being ‘liberators’.

However, this history is cast in a different light by Anzac Day – April 25th – and the Australian and New Zealand governments’ modern relationship with Turkey, what I call the ‘Special Relationship’.

For better or worse, Anzac Day is the most important day of nationalist celebration in both countries. And since the 1980s, the Anzac nations have built up a close diplomatic partnership with Turkey which includes official visits, memorials, speeches, and shared commemorations in Canberra, Wellington, or at Gelibolu itself. In one way, this close relationship is a rare example to the world: former enemies can be reconciled, and they can mourn together respectfully.

However, for thirty years Australian and New Zealand political leaders have defended this mythology and relationship with remarkable determination, to the point that they are prepared to deny the Armenian Genocide outright for fear of offending Turkey. In 2013, Ahmet Davutoğlu explicitly threatened that members of the New South Wales state parliament would not be allowed to attend ceremonies at Çanakkale because they had passed a motion of recognition. Rather than protest this threat by a foreign government, Australian leaders rushed to condemn the NSW state parliament for jeopardising the sanctity of Anzac Day and the ‘Special Relationship’.

Similarly, the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade has a permanent briefing file on this question which ministers and MPs consult when preparing to make public statements. This briefing file makes note of the 2013 threat, and clearly states that New Zealand will not recognise the Genocide in order to make sure Anzac commemorations “go smoothly.”

Of course, we’re well aware that the Turkish government is willing to use all kinds of diplomatic weapons against any country, human rights organisation, religious group, or academic who recognises the Genocide. But the Australia-New Zealand case is different. There are no significant defence, security, trade, or geostrategic issues at stake (like with the US or UK). It is purely a matter of politics, history, and memory. And all three nations, working together through this Special Relationship, have decided that mythology and nationalism are more important than truth and justice.

Official recognition of the Genocide could be a solution to this – just as the New South Wales parliament did, and as Green Party MPs are trying to do in New Zealand. But we would do well to remember Hrant Drink’s powerful observation that “denial or acknowledgement without comprehension benefits no one.” If Australian or New Zealand institutions do choose to recognise, it must be with a clear vision that they are challenging Turkey’s denialism, honouring their own Armenian citizens, and acknowledging their ancestor’s testimony and experience of that great crime. Otherwise, it is nothing more than an empty gesture.