‘Başarısız bir planın göstergesi bu boşluk’

‘Eğer biz Ermenice konuşmazsak, kim konuşacak?’ retoriğiyle büyür her Ermeni çocuğu. Anadili konuşman gerektiğinin absürd dayatması boynunun borcu olur dayatmanın sebebi anlaşıldıkça, dil giderek daha az kullanılmaya başlandığındaysa artık bir yüktür Ermenice. Dilin yüküne zamanla gelenekler, kültür ve din de eklenir. Özellikle Türkiye’de hakkıyla Ermeni olmak; kültürün ve dilin taşıyıcıları olmak, kimlik üzerine oturan ağır bir yüktür.

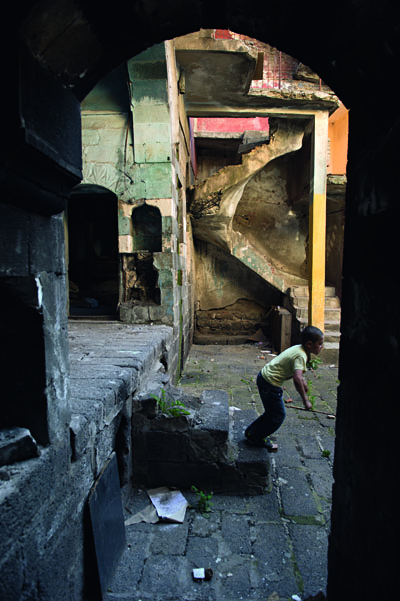

Norayr Şahinyan dünyanın diğer ucundan gelmiş buraya. 2012’den bu yana dört kez dolaşmış Anadolu’yu. Gezisi toplamda dokuz ay sürmüş. Bu gezinin fotoğraflarından oluşan bir kitabı var artık Norayr’ın; ‘Boşluğun Gücü’. İki hafta sonra İstanbul’dan ayrılırken üç yıldır edindiği sayısız dostu geride bırakacak, yanında ise kitabı ve enteresan hikâyeleri olacak.

Ermenilikten kaynaklanan bir deformasyon olsa gerek, kitaba bakar bakmaz aklıma bu ‘yük’ meselesi geliyor: “Yıllardır üzerinde çalıştığın bu projenin temelinde Ermenilik yatıyor. Ben Agos’ta çalışarak azaltıyorum yükümü, sen de bu geziyle belki… Öyle mi?”

Norayr bu geziye çıkmanın ona verilen bir vazife olduğunu anlatıyor: “9 yaşındayken dedeme söz vermiştim bir gün gelip Maraş’ı gezeceğim diye. Dedem Maraş’tan ayrıldıktan sonra bir daha hiç dönememiş, ‘bu yaştan sonra göremem ben, ama kalbimde hâlâ acısı durur, sen git gör oraları, konuş insanlarla’ demişti. Bana fotoğrafçılığı öğreten de oydu.”

Yeni bir dünya

Norayr ‘Boşluğun Gücü’nün basılıyor olmasının mutluluğunun veya haftaya açılacak sergisinin heyecanının ötesinde bir şeyler hissediyor. Sohbetimizde en az dört kez şu sözleri tekrarladığını fark ediyorum: “Köklerimi aramaya ve bana verilen görevi yerine getirmek için gelmiştim fakat bu görev için çıktığım yolda yeni bir dünyayla tanıştım. Bu tanışma beni dedemin verdiği görevi yerine getirmekten daha çok mutlu ediyor.” Norayr’ın ‘yeni bir dünya’ ifadesi, Diaspora’dan görünen Türkiye’yi düşününce daha anlamlı geliyor. 25 bin kişilik Brezilya Diasporası’nda Türkiye’ye ilk gelenin kendisi olduğunu anlatıyor Norayr: “Başlarına bir iş gelmesinden korkuyorlar. Ve tabii ki burası garip bir ülke, başlarına hakikaten bir şey gelebilir ama yine de…” Norayr buraya gelmeden, ona Türkiye’de öldürülebileceği, öldürülmese de kimsenin ona yardım etmeyeceği, Ermenice konuşan kimsenin ve de Hıristiyanların kalmadığı söylenmiş. O ise bunun mümkün olamayacağına kanaat getirerek atlamış gelmiş İstanbul’a. Elinde Agos’un adresi, bir de Baron Sarkis Seropyan’ın ismi…

‘Seropyan pusulamdı’

“Baron Seropyan benim pusulam oldu” diyor Norayr, Baron Seropyan’ı tanıyan herkesin söyleyeceği gibi. Ama Brezilya’dan gelen ve bu ülkenin dilini, yerini, insanını bilmeyen üstelik bunların bütününden korkan biri için eminim apayrı bir anlamı vardır bu pusulanın. Norayr ailesinin evini bulmak için yola çıktığında, doğal olarak insanların ilk tepkisi, duvarındaki yazı şöyle dursun, evin kendisini bulmasının bile imkânsız olduğunu söylemek olmuş. Bu yüzden de Norayr ona taşların ve tarihin yolunu gösterenlere, özellikle de Baron’a minnettar. “Bana şöyle yol tarifleri verirdi Baron: ‘Bitlis’e git. Oradan da şu köye... O küçük köyde iki kahve vardır. Sağdakine gir. Kahvede Ali’yi bul, beni ara, telefonu da Ali’ye ver.’” Baron’un o köyü avucunun içi gibi bilmesi, köydekilerle kurduğu yakın dostluk ve Türklerle bu şekilde ilişki kurulabildiğini bilmek Norayr’ın ‘yeni dünyası’nın parçaları.

Dedesinin dostu

Norayr’ın Adıyaman Gerger’de tanıştığı Ermeni aile, Diaspora’da söylenenin aksine, değil İstanbul’da Anadolu’da bile bugün hâlâ Türkiyeli Ermenilerin kimlik mücadelesi verdiğinin kanıtı: “Bakırcıoğlu ailesinin en yaşlı üyesi 96 yaşındaydı, Soykırımı görmüş. Bu kadının dördüncü kuşak torunuyla da tanıştım. Hâlâ Anadolu’da yaşıyorlar fakat kültürlerini ve dinlerini korumuşlar. Evlerinde 1900 yılında basılmış bir İncil var. Bu bana Anadolu’dan Ermenileri silme planının başarısız olduğunu gösteriyor ve bundan büyük güç alıyorum.”

Hayatına yön veren en azından onu anlatılmaya değer kılan çok ilginç tesadüflere sahip Norayr. Bunlardan biri malum, ailesinin Urfa’daki evinin duvarına 1922’de, ailenin diğer üyelerini bulması ümidiyle bırakılan mesaj. Diğeriyse, Norayr’ın 2014’te, Kesablı Ermenilerle konuşmak için Vakıflı’ya gittiğinde tanıştığı Hagop Amca’yla (Giragosyan) olan hikâyesi: “Annemin bir tarafı Kesablı. Diğer tarafı da Vakıflı’ya çok yakın olan Soğukoluk köyünden. Aslında biraz da bu yüzden tanışmak istedim o insanlarla. Oraya vardığımda bana fotoğrafçı olan Hagop’la konuşmam önerildi. Hagop’un 1950’lerde ve 60’larda Kesab’tan Halep’e fotoğrafçılık malzemeleri almak için gittiğini öğrendim. Halep’te alışveriş yaptığı fotoğrafçı dükkânıysa dedemin dükkânıymış. Dedemi tanıyordu. Benim boynumdaysa dedemin kamerası asılı… Kameramın, arkadaşının kamerası olduğunu öğrendiği anda gösterdiği duyguları asla unutamam.” “Düşünsene” diyor Norayr; “Ben kalkmışım Brezilya’dan Vakıflı’ya gelmişim. O da elinde yalnızca evinin anahtarıyla, her şeyini bırakıp Vakıflı’ya gelmiş bir mülteci. Ve birbirimizi bulduk.” Benimmiş gibi anlatabilmek için Norayr’dan dinlemek istiyorum bu hikâyeyi. Norayr’ın fotoğraflarına baktığımda da benzer bir hissi duyuyorum, keşke kamerasıyla yakaladığı bu anlar benim olsa…

‘Bu ev Der Bedrosyanların!’

Hep iyi şeylerden konuşuyor Norayr, sorana kadar da hiç anlatmıyor gezinin zorluklarını. “Her ne kadar ‘iyileşmek’ için gelmiş olsan da, ailesinin evini, duvardaki mesajı, yıkıntıları ve ‘boşluğu’ gördüğünde sinirlenmişsin olmalısın” diyorum, “herhalde!” diye ah çekiyor. Bazen her şeyi bırakıp kaçası, Brezilya’ya dönesi, tüm bu soykırım mevzuundan uzaklaşmak istediğini anlatıyor. “Ailemden 32 kişi öldürüldü, sadece iki kişi kaçabildi. Biri dedem. Onların bir zamanlar yaşadığı evi gezmenin nasıl bir şey olduğunu hayal edebilir misin? Üstelik bir de evin kapısında ‘bu ev I. Dünya Savaşı’nda varlıklı bir işadamı olan Mustafa Hacı’ya aitti’ gibi bir tabela görürsen… Hadi be oradan. Bu ev Der Bedrosyanların evi!”

O evde, o mesaja o kadar yakın uyumanın onu azıcık çılgına çevirdiğini anlatıyor Norayr. Çok fazla kişi, evi almak için dava açması gerektiğini söylese de Norayr’ın ev çok umrunda değil, Brezilya’da evi varmış, ne yapacakmış bu evi? İstediği sadece gerçeklerin yazılı olduğu bir tabela, “muhtemelen bu evi almaktan daha zor olacaktır” diye iç geçiriyor. “Yani üzücü bir projeydi bir yanıyla. Aylarca kendi başıma, dil bilmeden, Diaspora’dan gelen korkuyla gezdim. Zor ve üzücü anlar oldu. Yine de sürekli bir şeyler beni geri çekti.” “Bu senin görevindi çünkü ondan bırakamamışsındır” diyorum, “Öyleydi” diyor ve ekliyor “Bir de tabii yeni duvarlar, yeni taşlar, yeni insanlar tanımak vardı işin ucunda.” Bir kez daha görüyorum ki Norayr’ın en az önemsediği dedesinin ona verdiği görev.

Taşlara, duvarlara olan merakı sanıyorum mimar olmasından. Peki ya insanlar? Norayr’ın Anadolu’da karşılaştığı insanlarla ettiği sohbetlerin satır araları çok şey söylüyor: “Alakamın olmadığı insanlarla tanıştım yolda, bazen bir kelime, bazen de bir bakışla anlaştık, birbirimizi anladığımızdan emin olarak, konuşarak iyileştik birlikte. Urfa’da veya Maraş’ta bana bakıp ‘Bu adam bu topraktan’ diyorlardı. Onlara benziyorum diye mi? Genlerde mi bir şey var? Benim Brezilya’dan geldiğimi öğrendiklerinde hikâyemi daha da ilgiyle dinliyorlardı. Konu doğal olarak 1915’e geliyor ve kurtulan Ermenilerin Brezilya’ya kadar gittiğine inanamıyorlardı.”

Konuşul(a)mayan hikâyeler

Geçmişi bilmeyen birinin böyle bir hikâyede aklına binlerce soru gelebilecekken Norayr’a hiç soru yöneltilmemiş olması her zamanki gibi konuşul(a)mayan hikâyeleri işaret ediyor. Norayr bir de kendisinden özür dileyenler olduğunu anlatıyor: “Ülkenin çoğunluğu özür dilemiyor biliyorum, ama Soykırımı kabul edenleri bir de üstüne özür dileyenleri gördüğümde şok oldum. Artık bu sorunun siyasetle çözülemeyeceğinin farkındayım. Türkiye’deki insanların sözü değiştirecek bu durumu.” Bu sözlerden çözümün boşlukta yaşamaya devam eden insanlardan geleceği fikri bir daha ortaya çıkıyor, Norayr fotoğraflarının yalancı bir tarih kitabından çok daha fazla şeyi anlatacağından emin. Ailesinin evinin duvarında bulduğu mesajını anlamak isteyenlere çok şey söylediğini biliyor.

En başta sormam gereken soruyu en sona saklıyorum, bu boşluk ne? “Ermenilerin yokluğundan doğan bir boşluk olsa da, Ermenilere dair işaretler veya onların varlığını hâlâ ayırt edilebiliyor. Diğer taraftan başarısız bir planın da göstergesi bu boşluk. Plan Anadolu’yu Ermenilerden temizlemekti ve görüyorum ki bu topraklarda sadece Müslümanlaştırılmış Ermeniler değil, dinini geleneklerini koruyan, devam ettiren Ermeniler de var. Boşluk bir duvar da olabilir, bir insan da; tarihini veya köklerini bulmaya çalışan birisi de. Ve sadece üzüntünün ve acının göstergesi değil, yaşamın ve umudunda boşluğu bu.”

Norayr Chahinain’ın kitabında yer alan fotoğraflarından oluşan ‘Boşluğun Gücü’ sergisi 24 Nisan – 31 Mayıs arasında Tütün Deposu’nda ziyaret edilebilir.