Moving beyond the black (and dark) spots of history

What a wonderful statement from the Foreign Minister of Turkey, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu:

“Sözcükler tarihi değiştiremez, yeniden yazamaz. Tarihimiz hakkında kimseden ders alacak değiliz. Siyasi fırsatçılık barış ve adalete karşı en büyük ihanettir. Tek dayanağı popülizm olan bu açıklamayı tümüyle reddediyoruz.” For years Turkish government officials, and so-called historians (usually diplomats), repeatedly answered accusations that the Ottomans had committed a genocide against their Armenian and Assyrian subjects by insisting that these “controversial” questions be left to historians. But now Çavuşoğlu has made it clear that the Turkish government is “not going to take lessons about our history from anyone.” So, the new position in the highest circles of the Turkish government is to close their ears and eyes, to hear nothing, see nothing, and learn nothing. Ankara will not even listen to historians in Turkey, a whole new generation of young (and some older) scholars trained to read Ottoman texts, historians who have worked in the Ottoman archives, some of whom know not only Osmanlıca but Armenian as well. What can one say about a government dedicated to ignorance?

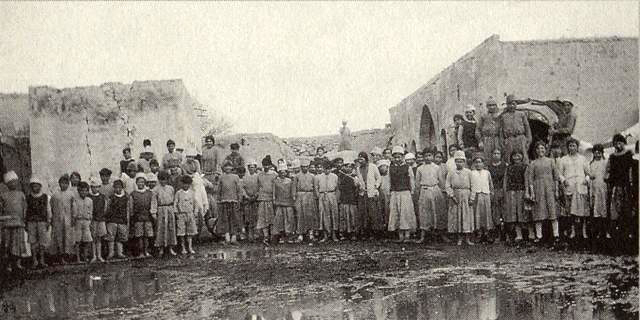

After President Biden’s statement on April 24 – the anniversary of the deportation of Armenian intellectuals and politicians from Istanbul that marks the symbolic initiation of the Genocide – Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan spoke to the High Advisory Council about what he considered the shameful distortion and misunderstanding of history by the American president. Ironically, Erdoğan spoke in the beautiful Çankaya Palace, a mansion in the center of Ankara that had belonged to a wealthy Armenian before appropriated as the home of the president of the republic. Ankara Armenians had suffered in the deportations of 1915, but because most of them were Catholic rather than members of the Armenian Apostolic Church, their exile and death was delayed for a time. Two years later a great fire swept through Ankara, and much of the Armenian neighborhoods burnt to the ground, a final blow to a community that would never return to the newly dedicated capital of the Kemalist regime.

Many of my friends and colleagues ask me, why are Turks and their government unable to recognize what happened in 1915 as a genocide? Why can they not simply acknowledge the factual truth that the ruthless Young Turk government that ruled in the final years of the Ottoman Empire carried out a brutal ethnic cleansing and mass murder of their Armenian and Assyrian subjects in a frenzied time of imagined danger to their regime? They are willing to admit that massacres occurred, that hundreds of thousands were killed or starved to death, that the Armenian population of eastern Anatolia was uprooted from their homes never to return. And yet they cannot bring themselves to recognize that the imperial government, the predecessor of the Republic, carried out such vicious crimes.

There are several answers that have been offered to these questions. The distinguished Dutch Ottoman historian Erik J. Zürcher has shown incontrovertibly that there was a stronger continuity between the Young Turks and the Kemalist republic than we had earlier realized, that many high-ranking Young Turk officials somehow found their way into the government in Ankara, and that much of Kemalist ideology was indebted to the Turkic nationalism of Young Turk ideologues like Ziya Gökalp. Mustafa Kemal himself was not involved in the Genocide, but many of those who worked with him were.

My own explanation is that it is difficult to recognize the Genocide because it blackens the foundational myth of the Turkish Republic. In the official telling of the founding of the Republic, Turks defended their homeland in a brave Kurtuluş savaşı against foreign enemies – Armenians, Greeks, and the Western Allies -- who wanted to destroy and divide the Turkish homeland in Anatolia. What is left out of this story is the process by which Anatolia became a Turkish or Muslim homeland with the elimination by mass murder of Armenians and Assyrians and the forced population “exchange” some years later of Anatolian Greeks. An ethnically Turkish (or Muslim, if one includes the Kurds) nation was built by the state after population removals occurred.

In many parts of the world modern nations have been founded after ethnic cleansing or genocides. Think of the United States, Australia, and Israel. That process of making homogeneous ethnonational states goes on around the world because people find it difficult to imagine multinational, multi-religious states, like the empires of old. The Ottoman Empire in fact, like its principal enemy, the Russian Empire, was made up of many different peoples and religions who managed for centuries to live together – not always peacefully. Some peoples were thought to be superior to others, but there was at the same time a certain degree of acceptance and recognition of difference – until the exclusivist Turkic nationalism of the Young Turks prevailed. How different our modern ethnonational states are today! In present-day Turkey nationalists insist on the dominance of a single people, the Turks, and treat other peoples as second-class citizens, even as colonialized subjects. The future of Turkey lies not in new forms of imperial subjugation but in a democratic, egalitarian amalgam of diverse peoples living together in a modern, tolerant, multicultural society that celebrates the variety of cultures and experiences of its citizens.

April 27, 2021