Curiosity, interest and suspicion meet Fatih Akın as he travels to Yerevan for the premiere of his latest film ‘The Cut’ in Armenia.

Renowned film director Fatih Akın had visited Armenia for the first time in 2010 for the Golden Apricot Film Festival, and had promised he would return with a film on the Genocide. Akın kept his promise, and five years later arrived in Yerevan for the premiere of his latest film ‘The Cut’.

The film is being shown in Armenian with the title ‘Sbi’ (Scar), and the press screening was held on 30 January at the Cinema Star Movie Hall. Akın’s 3-day visit was organized by The Republic of Armenia State Commission on the Coordination of Events for the Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, and the director also visited the Genocide Memorial and the newly-opened United World College (UWC) in Dilican.

Yerevan welcomed the first director of Turkish origin to make a film about the Genocide with interest, curiosity and suspicion. The interviews with Akın in the media made a great impact.

Nazaret ‘selfish’, his wife ‘ugly'

The press conference held after the screening on January 30 was attended by Fatih Akın, and also co-scriptwriter Mardik Martin, actress Arevik Martirosyan and producers Ruben Dishdishyan and Aram Movsesyan. Mosy journalists and film critics in Armenia watched the film with the question ‘Does it convey the Genocide sufficiently?’ in mind, and their questions often revolved around this issue. The first question to Akın was why he wanted to make such a film.

Akın stated that he found it very important that the film had been screened in Turkey, and that many young people had said, “We did not know that such things happened” and began to research the issue. Akın added that freedom of expression still did not exist in Turkey, that certain issues were only being spoken about recently and that change had accelerated after the assassination of Hrant Dink.

Some journalists claimed that the protagonist Nazaret had been portrayed as selfish, greedy and a thief, and that the film intended to depict a negative image of Armenians. Akın also faced the criticism that the film was not about the Genocide, and that a balance had been sought in the film between the murder, rape and theft of Turks in 1915 with the repetition of similar crimes by Americans or Armenians. Some journalists commented that they had not liked the film because they thought Nazaret’s wife had been specifically depicted as ‘ugly’.

Films cannot apologize

Akın responded to the question, “In the script, the Turk who wounds Nazaret apologizes to him. Is this a message of apology to the Armenians?” by saying, “A film cannot apologize. This is not only your Genocide; it is also my Genocide. This question is part of my everyday life; I told my own story with this film. Only a crippled girl and a mute father survive from a huge family, I think that is what we should focus on”.

Stating that his father was a supporter of the MHP, the Nationalist Movement Party, Akın said that he knew very well how the wider masses in Turkey thought, and that during the production of the film, his family, friends, and even his non-Turkish wife had tried to prevent him from making the film by saying, “Fatih, we have children, do you have to go through with this?” The director added that he was well known and loved in Turkey, but that he had received some negative reaction as well after making this film.

Five years with the Genocide

In response to claims that the film did not convey well how the Genocide was planned and executed, and that it appeared as if Armenians had died because of an unknown reason, Akın explained that over the 5-year preparation for the film, he had spent his time immersed in the film, and that it was not necessary to include all the information in the film. Akın gave renowned director Roman Polanski’s 2002 film ‘The Pianist’ as an example, stating that the film conveyed a life story, and that it was a very powerful movie although it did not provide factual information about the Holocaust.

There were also some who found it important that a film director of Turkish origin had made a film about the Genocide. The majority of those who watched the film thought that the most powerful metaphor in the film was the way in which Nazaret had been rendered mute and silent because of the wound inflicted upon his throat.

Notes from Akın’s visit to Armenia

- Co-scriptwriter Mardik Martin said, that when Akın asked for his help for the script, the thought that passed through his mind was “God has sent him to me”, and that to write a script about the Genocide was one of his greatest wishes.

- President Serzh Sargsyan and members of the Republic of Armenia State Commission on the Coordination of Events for the Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide also attended the premiere of the film held on 30 January at the Moscow Movie Theatre.

- Actress Arevik Martirosyan said that she found it very important that a director of Turkish origin has made a film about the Genocide, and that when she heard that Akın was looking for an Armenian actress who could speak English, she accepted the offer with great happiness.

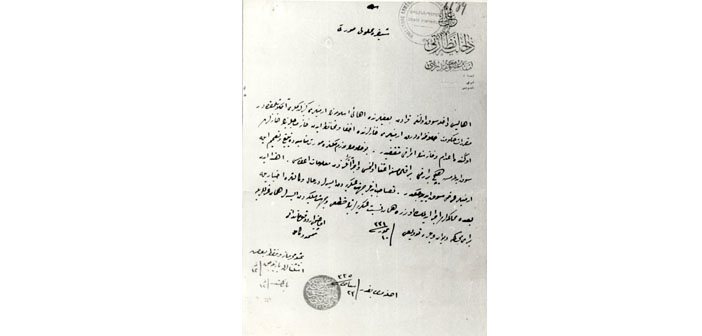

- Akın also visited the Genocide Memorial (Dzidzernagapert) and Museum in Yerevan. Akın said that he had met with Genocide Institute Director Hayk Demoyan during his previous visit, and that it was the cut on a sculpture of a tree at the museum that had inspired the title of the film.

Film critics from Armenia on ‘The Cut’

‘Armenians have been mute like Nazaret for a hundred years’

(Artsvi Bakchinyan, film critic)

We understand that Akın does not have the goal of proving a political case, or that the Genocide took place. He departs from a family story, trying to make a melodrama, or an adventure film, and he succeeds. Precisely as he says in his story, we Armenians have been mute like Nazaret for a hundred years. I believe this film will have a positive effect on the viewer who does not know anything about the Genocide.

‘The viewer forgets the real event’

(Siranush Galstyan, film critic)

The jolting, shocking scenes in the beginning of the film gradually ease off, and by the end of the film, the events are forgotten. I think that is the weak part of the film. The film turns into a story of a search, and the viewer forgets the real event. As for the part of the film I find most important, is that it may create curiosity about Armenia and the history of Armenia.