Rakel Dink, in the article titled ‘A Century of Genocide’ she wrote for the April 24, 2015, issue of Cumhuriyet newspaper, relates what befell her family and relatives in 1915, how she met Hrant Dink, and the struggles they put up together: Today, first at Balıklı, at my Çutak’s grave, then in Şişli, at Sevag’s grave, and finally, in Taksim Square, to commemorate the ones we lost during the 1915 Genocide, I will silently wait for this country to become free.

Today, the day you read this article, is April 24. A heavy, and very painful day of mourning. Today, I will briefly try to write for you, with the help of God, my own story.

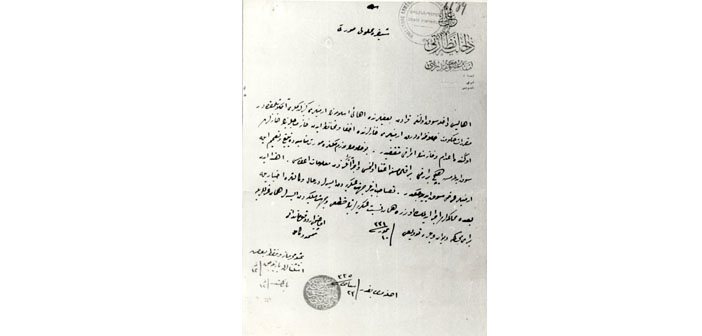

I was born in 1959, in the Armenian Varto Tribe, which is today administratively linked to Şırnak. Today its name has been changed to Yolağzı Village. Varto is the name of my father’s grandfather; it comes from the name Vartan. Back in the day, my great grandfather Vartan migrated to this area from Van. The lands of the tribe are in the southern foothills of Cudi Mountain. Close to the borders with Iraq and Syria. The Cudi Mountain presents a majestic view when seen from our lands. And from our neighbouring Hasana Village, the mountain appears as if it has spread its wings over the land. Today, neither the Hasana Village, nor the Armenian Varto Tribe exist. In 1915, the firman (edict) for destruction arrived. In our tribe, they used to call it ‘Fermana Me Xatibi’, in Kurdish. Our tribe managed to survive this firman with the help of an Arab Muslim tribe we knew as the “Tribe of Tayans”, in the depths of the Cudi Mountain, hiding for many years in the highlands, in coves and caves. “Cudi is the name of a saint. Christ protected us for her sake,” the elders used to say. In fact, there is even a legend claiming that the caves they sought shelter in did not actually exist...

Did she fall prey to the wolves, or perhaps to the birds?

As they escaped in 1915, the newly born child of a relative began to cry, and could not be silenced. The mother-in-law said, “You keep walking, pass the baby to me, my daughter,” and took her, and then... I can’t utter the words, you can guess what happened. That baby was the child of my maternal grandmother’s elder sister... Another person in the convoy could no longer carry their daughter, blindfolded her, and left her below a tree. They placed a piece of dry bread in her hand. They blindfolded her so when harm did come, she was not afraid. Every time they tell this story, they begin to cry, saying, “Did she fall prey to the wolves, or perhaps to the birds”. Who knows? Maybe she is the grandmother of one of you out there...

My father Siyament’s surname was Vartanyan, but it was changed to Yağbasan when the Surname Law came into force. My mother was Delal. They were both highly skilful people who did whatever they did in the best possible way, and they were courageous and honest. They made their living the hard way, never set eyes on other people’s property, never breathed a lie, and always defended what’s right, true and just. Even in the face of persecution. And they gave and taught us what they carried within themselves, setting an example with their very lives. My mother fell ill when she was 35. I was eight years old. She passed away into eternal peace. During that year a group of philanthropists visited our village. Encouraged by our Patriarch Shenork Srpazan back then, they travelled to the villages in Anatolia to find remnants of the sword. Since not a single Armenian school was left in Anatolia, their aim was to take children of a suitable age and bring them to Istanbul. Along with my father, Hrant Güzelyan and Orhan Yünkes brought 12 children to Istanbul. We were the second group. We were placed in boarding school to learn our language and religion and to receive education.

Our fathers would keep guard

When we were in the village, many nights, our fathers would keep guard. Dogs would howl. It seemed as if a spirit of fear wandered. Of course, they tried not to let the children realize, but you would sense it from their mood, and from the women’s incessant whispering of prayers, and you would see the anxiety. At different times, twice our shepherds were murdered. The week before the last remaining people of the tribe migrated to Istanbul, they murdered a man from the neighbouring Hasana Village, which was another Christian village, and hurled each part of his remains in a different corner. Fear gradually increased.

The agha of the neighbouring Dadar Village, a tenant of my father, had conjured up a fake deed and filed a lawsuit against my father. For 40 years, my father pursued these cases and the field surveys. He was injured many times, at times he tired, but he never gave up. My father passed away at the age of 72 in Brussels, while, to use your phrase, as a member of the “Diaspora” his “land demand” continued. The case is still open.

I met my beloved husband at boarding school. We first met at the summer residence of the boarding school, the Tuzla Armenian Children’s Camp. Together, we played knucklebones, we ran, we sang hymns, and we learned to help each other, to console each other, to cry with those who cried, to laugh with those who laughed, and to love and respect. We learned righteousness, honesty and sharing. We learned how to separate the good from the bad. On April 23, 1977, on Children’s Day*, we two children got married. Let me tell you something: We loved each other, and we loved to love.

In 1978, they shot our camp director Güzelyan. He was injured but survived. In 1979, they imprisoned him on the pretext of raising Armenian militants. We, a family with two children, took responsibility as directors of the camp during summers. Hrant was a student at university on the one hand, and our struggle to make a living continued on the other. In 1986, our third child was born. And then, the Tuzla Camp was seized by the state. It still stands today, dilapidated. I wish they had used it for a good purpose. They took it from us and gave it back to its former owner. Then it apparently changed hands several times. It brought no good to any of its new owners.

And the places in Istanbul where the children stayed were closed one by one during the winter.

Today, in this age of information, no one has the right to say ‘I don’t know’. My life story, or other people’s life stories... One observes how each person who survived during that period managed it only by a miracle.

There is even more to it than murder

These days, the pathetic Perinçek and his like make up stories saying, “Hrant did not call it genocide”. They have teamed up with state cadres in their pursuit for “freedom of expression”... Talaat Pasha and his friends... Thus we see that there is even more to it than murder. We saw the trials that took place after 19 January 2007. And at those trials I saw the anger and hatred that is not satiated by murder.

My dear Çutak**... He wanted for you to reach the honour and greatness of seeing the consequences through your own means, and he wanted to do that without offending you. Because he was good. He loved you very much. His wish and aim was to help you. We have seen many guises of racism, heartless, blinded, and inhuman. In the middle of the courtroom, they kicked and stamped the remains of the dead. Both while we lived with the threats, and after the assassination. Is that not the mentality of the Genocide?

Saying “No one is left... They are all gone, that is all”, “I wish they had not left. They went, and with them, the abundance of the land disappeared as well”, “We got along well, it was external powers that sew discord” means nothing. It is necessary to sincerely recognize the atrocity that took place, the grave robbing, the evil in laying waste to all forms of intimacy, that all those rights you call the rightful share of the servant of God were trampled under foot, that belongings, property and dignity were destroyed and that no right whatsoever was protected.

Which heart can comprehend the magnitude of that whole?

What I know, what I have heard, what I have experienced are perhaps trivial. Perhaps they constitute a mere fraction of a larger whole. But which mind, which heart can comprehend the magnitude of that whole?

Now I stand and look. I observe how grotesque and ridiculous humanity looks in the garb of denial. Mine is a bitter smile. A smile turned sour, full of tears. A smile in part full of anger and expectation.

I observe the world in 1915. I cry bitter tears for all humanity, and its policies. I observe the humanity of 2015, and my soul wails inside me. My life is drained out. I observe my country. I am ashamed. I cry. A lump sticks in my throat. I cannot swallow. I let loose my voice. My tears flow from my chest. I speak to God, I pour out my grief to Him. And by faith in His name, I beg to Jesus. For Him to show mercy to humanity. To lead hearts to repentance. Then the Lord will descend upon the earth, and humanity will move on with sincere recognition. Hearts will unite, wounds will be salved, and healing and joy will come. And thus the old rotten mentality will be cast aside like a dirty ragged garment. People will become pure, redeemed; they will shed their weight and emancipate themselves from the noose of history.

Today, first at Balıklı, at my Çutak’s grave, then in Şişli, at Sevag’s grave, and finally, in Taksim Square, to commemorate the ones we lost during the 1915 Genocide, I will silently wait for this country to become free.

* April 23, in commemoration of the establishment of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey on that day in 1920, is celebrated in Turkey as Children’s Day.

** Çutak means ‘violin’ in Armenian. It is also Rakel Dink’s nickname for Hrant Dink, and a pseudonym Hrant Dink used when he began to write columns.