"Ermenilerin yerini Kürtler aldı"

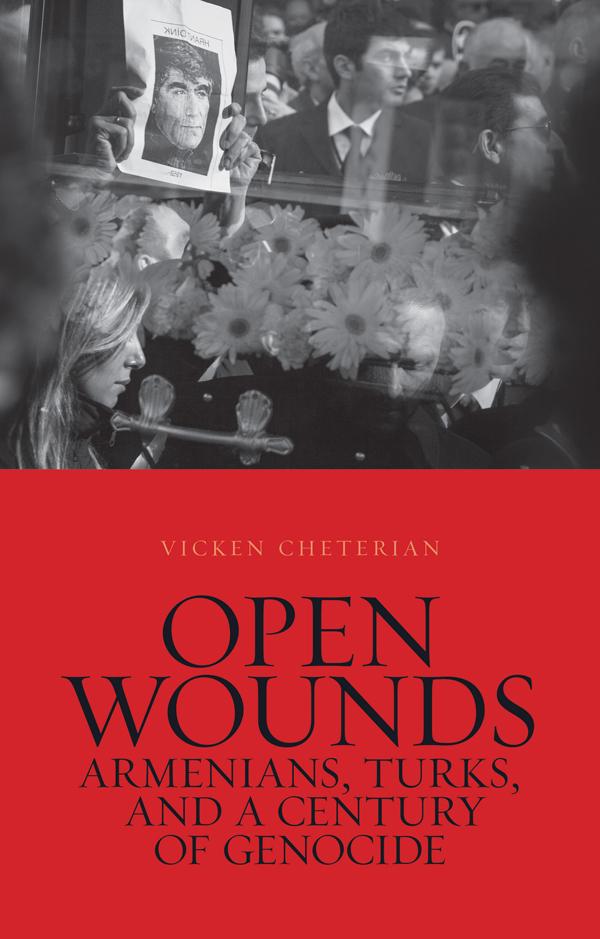

Size çok şey anlatan, öğreten kitaplar vardır da, olayları algılayış şeklinizi değiştirebilecek, toplumun iyileşmesini hızlandırabilecek kitaplara çok az rastlanır. İsviçre’de yaşayan gazeteci ve tarihçi Vicken Cheterian’ın yeni çıkan kitabı ‘Open Wounds: Armenians, Turks, and a Century of Genocide’ (Açık Yaralar: Ermeniler, Türkler ve Soykırımın Yüzyılı), kökten değişimleri tetikleyebilecek türden bir çalışma. Soykırımı geçmişte yaşanmış bir trajedi yerine, bugünün sosyal ve siyasi ortamında aktif rol oynayan bir olay olarak ele alıyor Cheterian. Ve bu suçun inkârının sadece yerel değil, küresel anlamda da derin yaralar açtığına dikkat çekiyor.

Soykırımın, inkârla, suçun ve gaspın meşrulaştırılmasıyla hâlâ devam ettiğini gösteren Cheterian, Türkiye’nin demokratikleşmesinin, Ermenistan ve Türkiye arasındaki ilişkilerin, Karabağ sorununun, Kürt meselesinin ve sadece bu coğrafyada değil tüm insanlık için önem taşıyan daha birçok çatışmanın altında 1915’in yattığına işaret ediyor. Ve ‘karanlık güçlerle savaşmak’ için soykırımla hesaplaşmanın hayati önemini vurguluyor. Henüz Türkçe baskısı olmayan kitabın yazarı Cheterian’la bir araya gelerek Ermeni Soykırımı’nın yüzyılını konuştuk; kitapta ele aldığı bazı çarpıcı noktaları bir de Agos okurları için değerlendirmesini istedik.

Ermeni Soykırımı’ndan bugüne kadar olan süreçle ilgili yazdığınız kitapta, Hrant Dink suikastini bir dönüm noktası olarak görüyorsunuz. Neden?

Aslında böyle bir kitap yazmayı hiç düşünmemiştim. Çünkü Ermeni Soykırımı hakkında yazılanları okumak bile bana acı veriyordu. Şimdi fark ediyorum ki, ben aslında çok uzun süre bu geçmişten kaçmaya çalışmışım. Hem annem, hem babam Türkiye doğumlu. Bense Beyrut’ta doğdum ve savaş yıllarında büyüdüm. Bu bağlamda kendimi, kıyıma uğramış, sınır dışı edilmiş, kültür ve uygarlığı yok edilmiş bir halkla ilişkilendirmek istemedim. Ne zaman soykırım anıları okumaya kalkışsam, acı çektim.

Bu kitap fikri, Londra’daki yayıncımdan geldi. Bir önceki kitabımla ilgili konuşuyorduk ve birden bana, “Neden soykırım hakkında bir şeyler yazmıyorsun?” diye sordu. Ben de o anda, “Soykırım hakkında nasıl yazabileceğimi bilmiyorum; çünkü zaten bu konuda çok iyi kitaplar var. Ama soykırım sonrası dönem ve insanlığın soykırım mirasıyla ne yaptığı konusunda yazmak isterim” diye cevap verdim.

Ardından bu konunun Türkiye’nin güncel durumuyla çok yakından ilişkili olduğunu gördüm. Taner Akçam, Ragıp Zarakolu ve Hrant Dink, yıllardır takip ettiğim ve tanıdığım insanlardı. Bu kitapta, son dönemlerde soykırım meselesinin neden bu kadar öne çıktığını anlamaya çalıştım. Türkiyeli entelektüeller ve daha birçok insan neden birdenbire bunun çok önemli bir konu olduğuna karar verdi? Yok edilen Osmanlı Ermenileriyle ilgili bu konuyu, Türkiye’de yeniden gündeme getiren değişimler neydi? Ve bunun olması neden bu kadar uzun sürdü? Ülkelerindeki bir tür boşluğun çoktan farkında olan Türkiyeli entelektüellerin, sanatçı ve şairlerin, 2000’lere kadar sessiz kalmasına yol açan koşullar neydi?

Bu yüzden de kitaba Hrant Dink’in öldürülmesiyle değil, cenazesiyle başladım. Onun cenazesinde on binlerce insan sokaklarda, “Hepimiz Hrant’ız, hepimiz Ermeni’yiz” diye bağırarak yürüyordu. Ben bunu, Türkiye kamuoyunda yaşanan bir devrim olarak görüyorum.

Burada sorduğum bir soru daha var: Bir toplumda, ülkede ya da köyde bir suç işlendiğinde, buradaki insanlar hiçbir şey olmamış gibi davranmaya devam ederlerse ne olur? Suç ortadan kalkar mı? Peki suçluya ve mağdura ne olur? Ben de bu suçun etkilerine bakmaya çalışıyorum. Projeye ilk başladığımda, genellikle Ermeni toplumuna odaklanacağımı düşünüyordum; hâlâ tanınmayan ve onları yıllardır kurban pozisyonunda tutan bu suça... Ermeni Soykırımı’nın ne zaman başladığını biliyoruz; ama ne zaman sona erdiğini bilmiyoruz. Çünkü soykırım henüz tanınmadı. Fakat sonunda bu durumun genel olarak Türkiye’yi ne kadar çok etkilediğini fark ettiğimde ben de şaşırdım.

“Hrant Dink, 1915’ten sonra Türkiye’de bir entelektüel olarak toplum içerisinde bir yer talep eden ilk Ermeni oldu. Kendinden önceki kuşaklardan farklı olarak, Ermeni kimliğini saklamak yerine, düşüncelerini ve duygularını özgürce ifade etmek istedi.”

Türkiye’deki entelektüeller arasında bir tür uyanıştan bahsediyorsunuz. Hrant Dink suikasti şüphesiz bu uyanışı tetikleyen en önemli etmenlerden oldu. Peki sizce bahsettiğiniz entelektüellerin ardından, Türkiye halkı da benzer bir uyanış mı yaşıyor?

Kitabın birinci bölümü Hrant Dink hakkında. O, Türkiye’deki Ermeni sorununa yönelik kamuoyunu gerçekten değiştirdi. Hrant Dink, 1915’ten sonra Türkiye’de bir entelektüel olarak toplum içerisinde bir yer talep eden ilk Ermeni oldu. Kendinden önceki kuşaklardan farklı olarak, Ermeni kimliğini saklamak yerine, düşüncelerini ve duygularını özgürce ifade etmek istedi. Bir taraftan da, bunu yaparken çok dikkatli davrandı. Türkiye’de geçilmemesi gereken bazı çizgiler olduğunun farkındaydı. Fakat o bu rolü üstlendiği andan itibaren, bu çizgileri de aşmak zorundaydı. Bu da öldürülmesiyle sonuçlandı.

Ben Hrant Dink’in tarihsel bir figür olduğunu düşünüyorum. Çünkü o, daha önce hiç kimsenin cesaret edemediği bir şey yaptı. Diğer taraftan Ragıp Zarakolu, Taner Akçam ve Hasan Cemal gibi isimleri de unutmamak gerek. Ragıp Zarakolu önemli bir figür; çünkü yıllarca kitaplar yayımladı ve Türkiye’de akademisyenlerin, tarihçilerin ve entelektüellerin Ermeni meselesini konuşup tartışabileceği bir alan yarattı. Onun fikirlerine karşı olan insanlar bile, yayımladığı literatüre kayıtsız kalamazlardı.

Bir diğer önemli karakter ise Taner Akçam. Akçam, kendisini Ermeni Soykırımı araştırmalarına adayan ilk Türk akademisyen. Onun bu yolu seçmesine neyin yol açtığını veya bunu neyin mümkün kıldığını anlamak istedim.

Hasan Cemal, faillerin, yani etnik bir grubu tümüyle ortadan kaldırma kararını verenlerin tarafından geldiği için sembolik olarak çok önemli. Hasan Cemal neden ‘1915: Ermeni Soykırımı’ başlıklı bir kitap yazmaya karar verdi? Entelektüel yolculuğu nasıl oldu da onu bu noktaya getirdi? Bence bunlar, öncülük eden insanlar. Cesaretleriyle değişimi başlattılar. Fakat biz, henüz bu yolculuğun sonuna ulaşmadık.

Kitapta, Türkiye’deki Ermeni toplumunun sessizliğine işaret ediyor ve bu sessizliğin nasıl kırıldığından bahsediyorsunuz. Yani sadece Türk toplumunun tutumu değil; Ermeniler de değişiyor.

Ermeniler arasındaki sessizliğin farklı türleri var. Birincisi, geleneksel Ermeni Diasporası’nın 1965 yılına kadar, yani 50 yıl boyunca sessiz kalması. Bu sessizlik, doğrudan yaşanan travmanın bir sonucu değildi; aslında henüz hiç kimsenin onları dinlemeye hazır olmamasından kaynaklanıyordu. Üzerlerinde bir tür sansür uygulanıyordu. Örneğin, Franz Werfel’in ‘Musa Dağı’nda 40 Gün’ isimli kitabından, 1930’larda bir Hollywood filmi yapılacaktı. Fakat Türkiye devletinin uyguladığı baskı sonucunda, kitabın haklarını satın alan Hollywood stüdyosu, filmi yapmaktan vazgeçti. Soykırımdan kurtulan Ermeni Diasporası, olanları henüz kimseye anlatamıyor; sadece kendi içinde konuşabiliyordu. Bence bugün Ermenilerin soykırım hakkında çokça konuşmalarının nedeni de, 50 yıl boyunca susturulmuş olmalarıdır.

Diğer taraftan Sovyetler Birliği topraklarında yaşanan farklı türde bir sessizlik vardı; çünkü Stalin soykırım anısını bastırdı. Kendisi de suçlu olan bir lider olarak, yönettiği imparatorlukta böyle bir yaşanmışlığın konuşulmasını, araştırılmasını ve anılmasını istemedi. Kemalist hareketle Sovyetler Birliği arasında da güçlü bir ittifak vardı. Kemalist hareket, Fransız ve İngiliz birliklerine karşı savaşmak için Sovyetler Birliği’nden para, cephane ve silah yardımı alıyordu.

Son olarak, Türkiye’de daha uzun süren bir sessizlik söz konusu. Aslında Türkiye sınırları dahilinde karşılaştığımız sessizliğin de farklı türleri var; İstanbul’da yaşayan Ermenilerin sessizliği, Bitlis, Diyarbakır, Antep’tekilerden, Anadolu’nun Müslümanlaştırılmış Ermenilerinden farklı. Bugün yıllarca gizledikleri Ermeni kimliklerini açıklayan ve bu kimliğe yeniden sahip çıkan çok sayıda insan var. Ve biz bu sürecin gelecekte nasıl ilerleyeceğini henüz bilmiyoruz.

Bununla ilişkili olarak kitapta, Rize’deki Hemşinlilerin Ermeni kökenlerinden bahsediyorsunuz. Geçmişe dair bu tür alternatif anlatıları gün yüzüne çıkarmak, sizce süreci nasıl etkileyecek?

Şu anda, Türkiye’nin demokratikleşmesi ve sessizlik duvarının kırılması süreçleri el ele, beraber ilerliyor. Yüzyıllar boyunca susturulmuş olan bu insanlar yavaşça ortaya çıkacak ve Ermeni kimlikleri üzerinde yeniden hak iddia edecekler. Fakat bunu yaparken, farklı yollardan ilerlediklerine dikkat çekmek gerek. Örneğin ben, Diyarbakır ve Gaziantep’te sadece Ermeni miraslarına yeniden sahip çıkmakla kalmayıp, bir de tekrar Ermeni Apostolik Kilisesi’ne dönen insanlarla tanıştım. Bir diğer grup da Ermeni kökenlerini araştırıyordu; fakat İslam dininden vaz geçmiyordu. Bunların yanı sıra, 17. yüzyılda Müslümanlaştırılmalarına rağmen, yaşadıkları Kuzeydoğu Anadolu’nun dağlık bölgelerinde anadilleri olan Ermeniceyi koruyabilmiş olan Hemşinliler var. Hıristiyanlık dinine geri dönmek gibi bir arzuları olmasa da, gün geçtikçe Ermeni geçmişleri ve kültürel kökenleriyle ilgili farkındalıkları artıyor. Bu da, siyasi otoritelere, karanlık 20. yüzyıl boyunca bu ulusu hâkimiyeti altında tutan totaliter ideolojiye meydan okuyan, sıra dışı bir durum.

Sizce 2015’te, soykırımın 100. yılında Türkiye’de neler oluyor? Bununla ilgili gözlemlerinizi paylaşır mısınız?

Bence Türkiye bu konuda ilerleme kaydetti; ancak hâlâ tereddütlere sahip. Türkiye, ancak kendisi hazır olduğunda adaleti sağlayacak. Kendi vatandaşlarına saygı göstermeye başladığında, geçmişte sistematik bir biçimde öldürülen eski vatandaşlarını da saygıyla anabilecek. Fakat Türkiye henüz bu aşamaya ulaşmış değil. Kemalist modelden uzaklaşılıyor olsa da, nereye doğru gittiğini henüz tam olarak bilmiyoruz.

Soykırımın geçmişte kaldığını söyleyemeyiz; o bugün, hâlâ bizimle. 100 yıl önce yaşanmış olsa da, henüz bu yaşanmışlığın üstesinden gelebilmiş değiliz. Türkiye Devleti geçmişte bir şeyler yaşandığını ve ortada bazı kurbanlar olduğunu kabul ediyor. 2014 Nisan’ında, o dönemin başbakanı Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Ermenilere taziye dileklerini iletti. Bu durum, ilk defa Türkiye’deki yetkili bir makamın Ermeni toplumunun yaşadığı acıları tanıması anlamına geliyordu. Fakat yine de bu, tuhaf bir tanıma şekli. Çünkü birbirleriyle savaşırken ölen askerler ya da katiller, soykırım kurbanlarıyla aynı seviyede kabul ediliyorlar. Öldürme eylemi ya meşrudur ya da suç. Bence Başbakan bir suçla, askerler arasında geçen mücadeleyi birbirinden ayırmayı başaramadı. Bugüne kadar Türkiye’deki hiçbir yetkili makam, soykırımın sorumluluğunu üstlenmedi.

Ermeniler için bu bir tanınma meselesi; yüz yıllık acıya bir son vermek ve sembolik de olsa adalet elde etmek istiyorlar. Fakat Türkiye için bu bir demokrasi sorunsalı. Yüz binlerce insanın öldürülmesini ve mallarının gasp edilmesini meşru kılan bir ülkenin, demokratikleşmesi mümkün değildir. Böyle bir ülkede hukukun üstünlüğü söz konusu olamaz.

Diğer taraftan Türk toplumu da 1915’te yaşananların sadece Ermeniler için değil; genel olarak Türkiye için önemli olduğunu fark edecek noktaya henüz ulaşmadı. Bugün bu durum, Ermeniler, Türkler ve Kürtler için farklı açılardan önem taşımaktadır. Ermeniler için bu bir tanınma meselesi; yüz yıllık acıya bir son vermek ve sembolik de olsa adalet elde etmek istiyorlar. Çünkü soykırım öyle muazzam ki, adalete hiç yer bırakmıyor. Fakat Türkiye için bu bir demokrasi sorunsalı. Yüz binlerce insanın öldürülmesini ve mallarının gasp edilmesini meşru kılan bir ülkenin, demokratikleşmesi mümkün değildir. Böyle bir ülkede hukukun üstünlüğü söz konusu olamaz.

Peki Türkiye için bir sonraki aşama ne olabilir?

Bence farklı güç odakları, 1915 Ermeni Soykırımı’yla birlikte, Süryani ve Pontus Rum soykırımlarının önemini anlayacak. Bu sadece Ermeniler, Kürtler veya Türkler için değil; tüm insanlık için önemli. Çünkü küresel siyasi kültür, bu yaşananlardan dolayı çok büyük darbe aldı. Siyasi kültürümüzün seviyesi çok düştü. Bu suçun tanınması, şu anda büyük savaş suçlarının işlendiği Orta Doğu için acil olarak gerekli. Tanımayı reddettiğimiz ve geçmişte olanlar hakkında bir hafıza oluşturmadığımız sürece, tüm toplumların içine işlemiş olan karanlık güçlere karşı savaşmamız mümkün olmaz. Dolayısıyla önümüzdeki on yılda bir araya gelmeli, hem geçmişte yaşanan, hem de gelecekte yaşanması mümkün olan suçlara karşı birlikte nasıl savaşabileceğimizi keşfetmeliyiz. Türkiye, iki farklı yol izleyerek bu konuda lider olabilir ve ahlaki zemini işgal edebilir: Birincisi sembolik de olsa bu suçun islendiğini kabul ederek. İkincisi ise Türkiye’de bir Ermeni Rönesansı’nın yaşanması için zemin hazırlayıp, bu suçun doğurduğu sonuçları somut bir biçimde tersine çevirmeye çalışarak.

Çalışmalarınız bir taraftan soykırım sonrası döneme odaklanırken, diğer taraftan tarihsel sürece de bir göz atıyor. Ve belki de, geçmişte yaşananlarla güncel olaylar arasındaki bağlantıları açığa çıkarıyor. Geçmiş ve güncel bağlamı birlikte ele alırken yaklaşımınız neydi?

Bu kitap üzerinde çalışmaya ilk başladığımda, bir suç tanınmadığında o suçun devam edeceğini net bir şekilde ortaya koyabileceğimi düşünüyordum. Bu yüzden de Türkiye’de yaşayan Ermeni, Rum ve Süryanilerin çektiği acılara odaklanmayı planlıyordum. Fakat daha sonra gördüm ki, olay sadece bu etnik gruplardan ibaret değil; suçun faillerinin de kendilerine ait, ortak bir hafızaları var. Örneğin Türkiye Devleti’nin çok güçlü bir belleği var ve 1915’e dair anılar da bu bellekte duruyor. Hem kurbanların, hem de faillerin 1915’ten öğrendiği bir şeyler var. Faillerin bu olaydan çıkarımı şu: “Siyasi anlamda bir problemle karşılaştığım takdirde –Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Ermenilerin konumu da buydu– siyasi arenada, parlamentoda, kanunlara göre, müzakere veya reformlara dayalı bir çözüm bulmak yerine, insanları sınır dışı edebilir, katledebilir ve sonra da yaptıklarımı inkâr edebilirim. Çünkü sonuç idare eder.” Ve ardından bu tutum, siyasetin etkili ve meşru bir aracı haline gelir. Çünkü soykırım suçunu işleyen insanlar, hâlâ ulusal kahraman olarak anılıyorlar.

Eğer suç geleneğini gayrimeşru kılmak istiyorsanız, suçların kaynağına inmek ve bu suçu işleyen kurumun, devletin, derin devletin onu tanımasını talep etmek zorundasınız. Ancak bunun sonucunda, gizli komplo zihniyeti yerine hukuki yasalarla yönetilen bir devlet yaratabilirsiniz.

‘Şiddet, bir sabıka kültürü yaratır ve daha da çok acının yaşanmasına yol açar’

Ermenilerin sorunlarının çözümünü Kürt meselesiyle bağlantılı bir biçimde ele alıyorsunuz. Bununla ilgili kitapta, “Kurds: From Perpetrator to Victim” (Kürtler: Failden Kurbana) başlıklı bir bölüm de var. Ve bu başlık altında, eskiden Ermenilerin yoğun olduğu bölgelerin, bu tarihsel süreçte nasıl Kürtleştiği anlatılıyor. Türkiye’nin güncel siyasi atmosferini de göz önünde bulundurarak, bu durumu yeniden değerlendirir misiniz?

Bence bu konu Türkiye’nin demokratikleşmesiyle ve tabii ki Kürt meselesiyle yakından ilişkili. Diğer taraftan Ermenistan ve Türkiye arasındaki ilişkilerle ve Karabağ sorunuyla da alakalı. Biraz derine indiğinizde, 1915’in bu sorunların kökeninde durduğunu ve tüm bunlarda oldukça olumsuz rol oynadığını görürsünüz. Ermeni Soykırımı’nın tanınması için savaşmak, aynı zamanda insanlığa karşı işlenmiş suçların aklanması geleneğine karşı da savaşmak anlamına gelir.

Türkiye’deki Kürt meselesinin ortaya çıkışı, ülkenin güneydoğusunda yaşayan Süryani ve Ermenilerin yok edilişinin hemen sonrasına denk gelir. Bu da sorunların şiddetle çözülemeyeceğini gösterir; çünkü şiddet, bir sabıka kültürü yaratır ve daha da çok acının yaşanmasına yol açar. Kürt tarihininse metafizik bir boyutu vardır: 1915’te Kürtler faildi, 1920’de ise kurbana dönüştüler. Birçok anlamda Kürtler, Ermenilerin yerine geçti. Bugünkü demografik özellikleri bile, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda yaşayan Ermenilerinkiyle benzerlikler gösterir. Örneğin toplumun yarısı yoksul olan doğuda yaşar; diğer yarısıysa batıdaki büyük şehirlerde. Bugün Kürtler, Ermenilerin 19. yüzyılda yaptığı gibi, ayrımcılık yerine hukukun üstünlüğünün arayışındalar. Ermeniler 1915’te kaybetti; çünkü reform taleplerine yıkımla cevap verildi. Umarım Kürtler de aynı tehditle karşılaşmayacaklar ve Türkiye’nin demokratikleşme sürecindeki ana güçlerden biri haline gelecekler.