"Parçası olduğum Türkiye bu filme hazır"

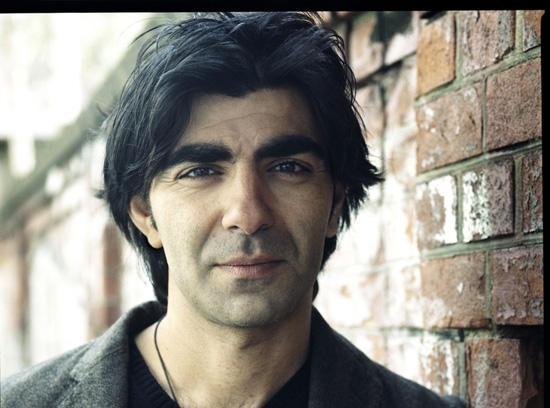

EVRİM KAYA

[email protected]

Fatih Akın’la Agos için ilk söyleşiyi, dört yıl önce, Altın Kayısı Film Festivali’nin konuğu olarak gittiği Yerevan’da yapmıştık. Uçaktan ineli çok olmamıştı, izlenimleri sınırlıydı. Ermenilerle ve Ermenistan’la ilgili pek bir şey bilmediğini fark etmişti konuşurken; yalnızca, Almanya’da yaşayan ve dünya şampiyonu olan iki boksör geliyordu aklına. Oysa Yerevan Fatih Akın’ı heyecanla karşıladı. Örneğin, her yıl festivale ev sahipliği yaptığından, dünya çapında pek çok yıldızı ağırlamış olan otelin resepsiyonunda çalışan genç kadın, ilk kez bir konuk geldiğinde mesaisinin başında olup onu karşılamayı umuyor, katılımcılardan Akın’ın geleceği saati öğrenmeye çalışıyordu. Fatih Akın filmleri Yerevan’da coşkuyla izlendi, o da her mülakatında sınırların anlamsızlığını vurguladı, sanatın tüm tabuları yıkıp insanları buluşturabileceğini anlattı. Söyledikleri doğruydu doğru olmasına, ancak Ermeni Soykırımı ya da Ermenistan-Türkiye sınırı sorulduğunda verilen iyi niyetli yanıtların ötesine gidemiyordu. Ne yapmalı sorusu olduğu yerde duruyordu. Sanat her şeyin üstesinden nasıl gelecekti? Bu sorular yanıtını aramaya devam ederken geçen dört yıl boyunca, bu konuda da, başka konularda da konuştuğunu pek duymadığımız yönetmen, Nisan ayında yeni filminden ilk haberlerle gündeme geldi.

Time Out Istanbul’un haberine göre, Fatih Akın’ın son filmi ‘The Cut’ (Kesik), “Mardin’de yaşayan Ermeni bir karakteri canlandıran Tahar Rahim’in, başına gelen bir trajedinin ardından kızlarını bulmak için çıktığı yolculuğu” anlatıyor. Oysa, yayının editörünün de bildiğine eminiz ki Tahar Rahim’in canlandırdığı Nazaret’in “başına gelen” o trajedi, Ermeni Soykırımı’ydı.

Fatih Akın’ın dört kıtaya yayılan bir coğrafyada, büyük bir bütçeyle, sessiz sedasız çektiği ‘The Cut’, 27 Ağustos-6 Eylül arasında yapılacak olan Venedik Film Festivali’nde ilk kez izleyicinin karşısına çıkacak. Filmde Rahim’e dünyanın dört bir yanından oyuncuların yanı sıra Simon Abkarian, Arsinée Khanjian, Kevork Malikyan gibi Ermeni oyuncular, Kıbrıslı Akın Gazi, Almanyalı Numan Acar, Faslı şarkıcı ve ozan Hindi Zahra ile Türkiye’den Önder Çakar, Bartu Küçükçağlayan gibi isimler eşlik ediyor.

Belki biraz, trajedilerin adını koyma konusunda pek becerikli olmayan Türkiye medyasının kafa karışıklığını giderme umuduyla, ama esasen, dünyanın her yerinde yeni filmini günleri sayarak bekleyen Fatih Akın hayranlarına taze bilgiler verebilmek için, bizim de yalnız fragmanını izlediğimiz filmle ilgili merak ettiğimiz her şeyi yönetmene sorduk. Film üzerine verdiği bu ilk söyleşide her zamanki açık kalpliliğiyle konuşan Akın, en büyük umudunun filmin Türkiye’de hak ettiği gibi büyük salonlarda gösterime girmesi olduğunu söyledi.

-

Dört yıl önce konuştuğumuzda Ermenilerle ilgili pek az şey bildiğinizi anlatmıştınız. Belli ki bu durum bir şekilde değişti. 1915’i ve Ermenileri anlatan bir film yapma fikri nasıl aklınıza düştü?

Aslında ‘Soul Kitchen’dan sonra Hrant Dink hakkında kurmaca bir film yapmayı planlamıştım. Hrant’ın Agos’ta yayımlanan yazılarından 12’sini temel alan bir senaryo yazdım. Bu avangart bir projeydi, çünkü yazılardan bazıları bilgilendirici makaleler, bazıları Hrant’ın kişisel anekdotları, bazıları da 1915’le ilgili anlatılardı. Metin zengini bir senaryoydu. İyi bir film olur muydu, bilmiyorum. Fakat hiçbir Türk oyuncuyu Hrant rolünü oynamaya ikna edemedim, hepsi senaryomu fazla sert buldu. O yüzden de projeyi dondurmak zorunda kaldım. Hiçbir oyuncuya zarar gelsin istemezdim, ama Hrant’ı anlatan bir filmin ‘Türk filmi’ olması da önemliydi. Hrant’ı bir Amerikalı ya da Fransız oynayamazdı. Bu konuyla kendimiz baş etmeliyiz. Demek ki zamanı gelmemiş... Hrant’ın 1915 üzerine yazdığı kimi yazılar çok büyüleyici, görsel olarak da çok güçlüydü. Mesela ‘Kertenkele Abdullah’... Yine Hrant nedeniyle, 1915 üzerine çok okumuş, çok araştırma yapmıştım. Gerçekleştirmek istediğim başka bir senaryo daha vardı: Amerika’ya giden Anadolulu gezginler üzerine bir hikâye; bir tür western. Sonuçta Hrant senaryosundan kimi parçaları bu Western’le birleştirdim ve ortaya ‘The Cut’ çıktı.

-

Filmi Martin Scorsese’nin efsanevi filmlerinde imzası bulunan, Iraklı Ermeni senarist Mardik Martin’le birlikte yazmış olmanız çok heyecan verici. Bu işbirliği ve yazım süreci nasıldı?

Senaryoyu Almanca yazmıştım. Filmi İngilizce çekeceğim belli olunca, senaryoyu Almancadan İngilizceye çevirmekten daha fazlasını yapacak birine ihtiyacım olduğunu anladım. Bana Amerikalı bir senaryo yazarı lazımdı; hem konuyu, hem de buraların dilini, âdetlerini bilen biri olması gerekiyordu bu senaristin. Aklıma Mardik Martin geldi. Scorsese’nin ekibi bizi bir araya getirdi. Mardik’i ilk kez telefonla aradığımda kabul etmedi, emekli olduğunu, 30 yıldır senaryo yazmadığını söyledi. Ama ‘The Cut’ı okuyunca vuruldu. Hayatı boyunca böyle bir filmin hayalini kurmuş! Yalnız, senaryonun ‘Amerikanca’ya çevrilmekten daha fazlasına ihtiyacı olduğunu da söyledi. Senaryoyu değiştirdi, kişiselleştirdi, düzeltti ve yoğunlaştırdı. Olumlu anlamda, daha ‘Amerikalı’ yaptı. Bu filmle bir yandan da, beni en çok biçimlendiren şey olan Amerikan sineması, özellikle –Mardik Martin’in de büyük payı olan– Scorsese sineması üzerine kafa yoruyorum. Mardik’le çalışmak hayatımı pek çok açıdan zenginleştirdi. Her şeyden önce, köklere, benim için önemli olan, sinemaya ve hayata dair her şeyin köklerine dönük bir yolculuk oldu bu. Mardik benim en yaşlı arkadaşım ve öğretmenim.

Yazma sürecini baştan anlatmam zor; iki-üç cümlede tarif edilemeyecek kadar karmaşıktı. Castro bir yerde devrimin üç özelliği olduğunu söylemiş: 1. Gözlemlemek. 2. Tasarlamak. 3. Harekete geçmek. Yazım sürecini en güzel betimleyen şey budur. Elbette bu film bir devrim değil, devrimci de değil. Ama belki de her yazma eylemi kişisel bir devrimdir.

Dünyanın her yerinde, bana araştırmalarımda yardım eden yüzlerce insanla buluştum. Örnek olarak iki kişinin adını vermek isterim: Benim gibi Hamburg’da yaşayan Wolfgang Gust ve Taner Akçam. Filmin en önemli kaynağı, bu iki araştırmacının bilimsel yayınları oldu.

-

Fragmandan, Tahar Rahim’in, sessizliğe gömülen bir karakteri anlatmak için çok iyi bir tercih olduğu anlaşılıyor. Oyunculara nasıl karar verdiniz?

Her zaman yaptığım gibi, bu film için de en iyi oyuncuları bulmaya çalıştım. Gereken orijinalliği yakalayabilmek için Ermeni rollerinde olabildiğince çok Ermeni kullanmaya gayret ettim. Ama onlarla sınırlı kalmadım. Şarkıcı, ozan Hindi Zahra’yla çalışmak istedim. Zahra Faslı ama filmde, Tahar Rahim’in oynadığı başkahraman Nazaret’in karısını canlandırıyor. Rahim içinse, Jacques Audiard’ın ‘Yeraltı Peygamberi’ filmini izler izlemez, “Aradığım adam bu” dedim. Tahar, Cezayir asıllı bir Fransız. Tüm içgüdülerim bana “İşte kahramanın bu, işte aradığın Ermeni bu! Nereli olursa olsun, senin için bu rolün altından kalkacaktır” dediği için ona verdim bu rolü. Katı kurallar yok çünkü, su akıp yatağını bulmalı. Birlikte çalışabildiğim Türk oyunculardan da çok memnunum. Bartu Küçükçağlayan kilit bir rolde. Bartu büyük bir adanmışlık, tutku ve zekâyla oynadı. Bir yandan da, ne kadar masum... Bunda müzisyen olmasının da payı var. Türkçe diyalogları yazan arkadaşım Önder Çakar da oynuyor filmde. Ayrıca Numan Acar, Korkmaz Arslan, Mehmet Yılmaz gibi Almanyalı Türkler ve Kıbrıslı İngiliz Akın Gazi var. Bu arada, Akın’ı mutlaka Yılmaz Güney rolünde oynatmak istiyorum.

Filmde, hep duduk sesiyle başlayan etnik dünya müziği olsun istemedik. Bizim müziğimiz Heavy Metal’di, çünkü anlattığım şeyler Heavy Metal’di. Filmden korkanlar varsa, onlara “Bu yalnızca bir film” diyorum. Ama şundan eminim ki, benim de bir parçası olduğum Türk toplumu bu filme hazır. |

-

Görüntü yönetmeni yine Rainer Klausmann, ama bu filmde kendi ustalığını da aşan bir performans sergilemiş gibi görünüyor. Çekimler nerelerde yapıldı?

Filmdeki anahtar motif, kahramanın yolculuğu. Filmdeki bu yolculuğu ben de baştan sona yaptım. Türkiye, Suriye, Lübnan, Küba, Florida, Minneapolis, Kuzey Dakota rotasında ilerleyip binlerce resim çektim, notlar aldım. Doğru çekim yerlerini bulmak uzun ve meşakkatli bir işti. En sonunda Ürdün, Küba, Kanada, Malta ve Almanya’da karar kıldık. Rainer de, ben de, ilk kez anamorfik objektifle sinemaskop çekim yapıyorduk. Ve tabii ki 35 mm! Bir rüyadan söz ediyorum size, bu film sahici bir şey. Öyle ki, bazen “Beni çimdikleyin, gerçek olduğuna inanamıyorum” diyordum. Bu kameranın objektifleri çok ağır olduğu için, yalnızca iki objektifle çalıştık; birini yakın planlarda, diğerini de geri kalan sahnelerin çekiminde kullandık. Film geniş bir coğrafyada geçtiği için, genelde geniş açılı objektif kullandık ve bu, filme bir ciddiyet kattı, klasik bir hava verdi. Güneşi hep arkamıza almaya gayret ettik. Bir yandan klasik olmaya, bir yandan da, görüntüde ve seste klişelerden kaçınmaya çalıştık. Sepya filtre falan gibi boktan şeyler de kullanmadık. Hep duduk sesiyle başlayan etnik dünya müziği de istemedik. Bizim müziğimiz Heavy Metal’di, çünkü anlattığım şeyler Heavy Metal’di.

-

Agos’ta bir süredir 1915’i hakkını vererek anlatan bir film neden çıkmadı diye konuşuyoruz. Oysa, örneğin Holokost’u anlatan çok büyük filmler var. Sizin aklınızda kalan Ermeni Soykırımı filmleri, size referans olan başka filmler var mı?

Filmimi soykırım üzerine bir film olarak görmüyorum. Soykırım üzerine bir film nasıl olur ki? Bu janrın retorik araçları nelerdir? Ya da ‘soykırım filmi’ diye bir janr var mıdır? Benim seçtiğim janr Western’di. Sergio Leone’nin, Eastwood’un janrında bir film, bir macera filmi bu. John Huston’ın, David Lean’in geleneğinden bir destan... ‘Schindler’in Listesi’ ya da ‘Ölüm Tarlaları’ geleneğine ait değil. Atom Egoyan bana birkaç kostüm ödünç verdi ama filmin ‘Ararat’la da ilgisi var diyemem. Filmin en büyük ilham kaynağı, Elia Kazan’ın ‘Amerika Amerika’sı oldu. Orda burda o filme de soykırım filmi dendiğini okudum, ben buna katılmıyorum. Bence ‘Amerika Amerika’ hem bir destan, hem de macera filmidir.

-

Bu filmi yapmak sizin için neden önemliydi? “Aşk-ölüm-şeytan üçgenini tamamlıyorum” demiştiniz. Fragmanda Tahar Rahim’in bir soruyu sessizce, bakışlarıyla yanıtladığı bir sahne var: “Bunu sana kim yaptı?” Sizin bir cevabınız var mı?

Bazen, ben konuyu seçmedim, konu beni seçti diye düşünüyorum. Nerede yasaklanan, tabulaştırılan, tehlikeli olan, ihtilaflı bir şey görsem, hemen ilgimi çeker. Nerede bir yasak varsa, orada korku vardır. Bu film korkunun sonuçlarını soyut bir şekilde ele alıyor. Şeytan dışımızda değildir, sinsice içimize sokulur. Zaten oradadır yani. Onu bir tek kendimiz kovup atabiliriz. Yaşlı adamın Tahar’a çölde sorduğu “Bunu sana kim yaptı?” sorusuna benim verdiğim yanıt, “Korku.”

-

Bu film Türkiyeli izleyiciyi, 2015’e girerken geçmişinin en karanlık sayfasıyla yüzleştirecek. Filmi merakla bekleyenler de var, korkuyla bekleyenler de. Onlara söylemek istediğiniz bir şeyler var mı?

Micheal Jackson’ın ‘Thriller’ şarkısının klibinin sonuna doğru bir sahnede, Jackson’ın kız arkadaşı korkudan ciyak ciyak bağırır. Bir anda MJ karşısında belirir ve “It’s just a movie” (Bu yalnızca bir film) der ona. Filmden korkanlar varsa, ben de onlara “Bu yalnızca bir film” diyorum. Ama şundan eminim ki, benim de bir parçası olduğum Türk toplumu bu filme hazır. Elbette böyle bir filmin sert olması gerekiyor, yoksa ciddiye alamazdık. Ama her akşam izlediğimiz haberler, filmden daha sert. İçerikten rahatsız olacak birileri çıkacaktır. Tam da bu yüzden, filmin, yapıcı bir tartışmaya vesile olacağını düşünüyorum ve izleyenleri, 1915 üzerine daha çok şey öğrenmeye teşvik etmesini, böyle bir şeyin tekrar yaşanmaması için düşünmeye sevk etmesini umuyorum.

-

Dört sene önce yaptığımız röportaj söyle bitiyordu: “Benim işim her zaman şunu ifade eder: Nerede bir sınır varsa yıkalım, duvara karşı, gegen die Wand! Yıkılmazsa da köprü kuralım. Siyaset her zaman kültür ve spordan sonra gelir. En yavaş işleyen şeydir. Her zaman önce kültür, spor, önce halk çözmüştür sorunları, sonra siyaset onu izlemiştir.” Bu film duvara karşı bir hamle ya da, bir köprü mü? Siyasetin çözemediklerini çözebilecek miyiz?

Filmi bir yerden bir yere gitme motivasyonuyla yapmadım. Politik bir amacın peşinden giden bir gruba dahil değilim ben. İnsanların filmimi izlemelerini istiyorum. En büyük umudum, filmimin hak ettiği şekilde Türkiye’de gösterime girmesi, büyük ve modern salonlarda izlenmesi. Eğer bunu becerebiliyorsak, demek ki olgun, aydınlık, kendi kendinin bilincinde ve demokratik bir toplumuz biz. Yapamıyorsak, bizi hâlâ korku yönetiyor, şeytan bizi hâlâ parmağında oynatıyor demektir.

“Benden ‘Yaşamın Kıyısında – 2’ bekleniyordu”

-

Filmin Cannes’a kabul edilmediğine dair haberler çıktı. O süreci anlatır mısınız?

Cannes, filmi hiçbir noktada reddetmedi. ‘Belli Bir Bakış’ bölümüne dahil etmeyi de teklif etmediler bize; böyle bir teklifi reddederdik. Diğer filmlerimin Cannes’da yarattığı belli bir imaj vardı, bu film ona uymadığı için Cannes kararsız kaldı. Benden yine Türklük-Almanlık meseleleriyle uğraşan, minimalist bir film bekleniyordu, ‘Yaşamın Kıyısında - 2’ gibi bir şey... Ama ben kimsenin beklentilerini yerine getiremem. Benim, kendi beklentilerimi karşılamam lazım. Cannes kararsız kalınca, daha Nisan ayında filmi Venedik’e gösterdim. Hemen, filmi programlarına dahil etmek istediler, ettiler de. Ama festivallerin programlarını kendilerinin anons etmesi gerekir; ben de bu bilgiyi bir süre paylaşmadım.

Cannes’ın takıldığı meselelerden biri, filmi neden İngilizce çektiğim sorusu oldu. Elia Kazan ‘Amerika Amerika’yı hangi dilde çekti? Bertolucci’nin ‘Son İmparator’unda Çinliler İngilizce konuşuyordu, filmdeki Çince, İngilizceydi. Polanski’nin ‘Piyanist’inde de Polonyalılar Leh aksanıyla İngilizce, Almanlar Almanca, Ruslar Rusça konuşuyordu. Nasıl oluyor da, Bertolucci ve Polanski’ye bu hak verilirken, ben yapınca sorgulanıyorum? İki yüzlü bir tutum bu.

Öncelikle, her şeyin gerçekten yerine oturup oturmadığını kendim anlayabilmek için, kendi konuşabildiğim bir dilde çekmem gerektiğinden, İngilizce çektim filmi. İkincisi, yalnız Batı Ermenicesi konuşan Ermeni oyuncularla değil, kimi istersem onunla çalışabileyim diye... Oyuncuların fonetik olarak ezberlenmiş cümlelere değil, duygulara odaklanması lazımdı. Mel Gibson’ın Aramice çektiği ‘Passion’ ya da Maya dilinde çektiği ‘Apocalypto’ gibi filmlere dilin fazladan bir şey kattığını düşünmüyorum. ‘The Cut’ta özdeşleştiğimiz dil İngilizce. Film yabancı dünyalara yapılan yolculukları anlattığı için de, diğer figürler kahramanımıza yabancı olan dilleri konuşuyorlar.