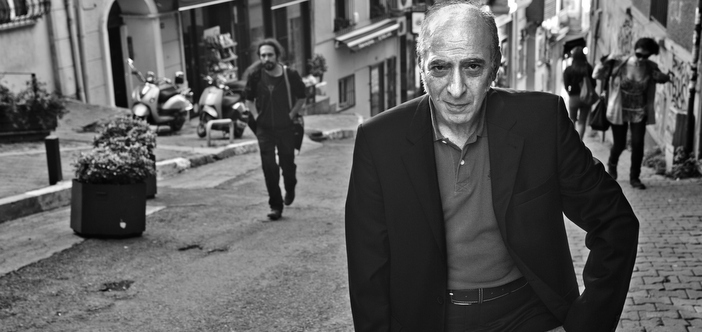

Kevorkian: Kabul etmenin yolu sorgulamaktan geçiyor

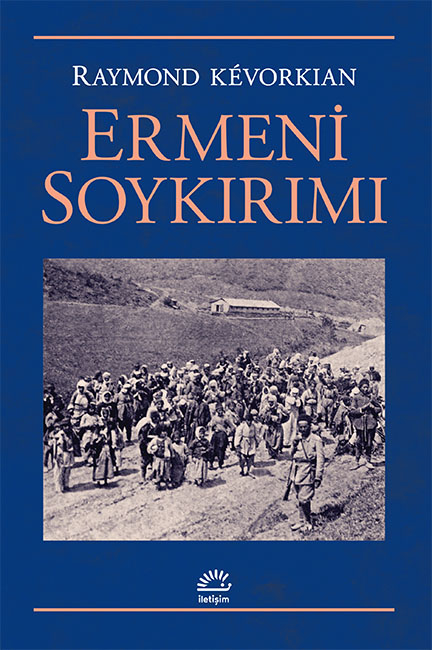

Kévorkian’ın, soykırımın, 19. Yüzyılın sonundan Türkiye Cumhuriyeti’nin kuruluşuna kadar süren safhalarını ele aldığı kitabının en çarpıcı özelliklerinden biri belki de, çeşitli yazışma ve tanıklıklara yer vererek, kıyımların gerçekleştiği yerleri, bölge bölge, köy köy, fail ve kurbanların isimleriyle detaylandırarak sunması…Kitabın oluşum sürecinin yanı sıra, Kévorkian’la, Türkiye’nin; Soykırım konusunda yürüttüğü politikaları konuştuk.

Kitabı Türkçe’ye çeviren Ayşen Taşkent Ekmekçi’yle yaptığımız söyleşiyi okumak için tıklayınız.

Bize biraz bu kitabın yazım sürecinden bahsedebilir misiniz? Araştırma ve yazma safhaları ne kadar sürdü?

Bu tarz çalışmalar genellikle uzun bir zamana yayılır. Öncelikle konuya ve kaynaklara iyice hâkim olmak gerekir, ki bu da her zaman kolay bir süreç değildir. Kitabın çatısı yavaş yavaş şekillenir. Bu çalışmanın hazırlık süreci yaklaşık yirmi yıllık bir süreye yayıldı diyebiliriz. İlk olarak Osmanlı Ermenilerinin demografik durumunu ve Osmanlı topraklarındaki mevcudiyetlerini incelemeye başlamıştım. Bu araştırmanın sonucunda, Türkçesi de üç yıl önce İstanbul’da yayımlanan bir eser ortaya çıkmıştı (Paul Paboudjian’la ortak çalışma, ‘1915 Öncesinde Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Ermeniler’, Aras Yayıncılık). Ayrıca, soykırımın ‘ikinci aşaması’, başka bir deyişle, tehcir edilenlerin Suriye ve Mezopotamya’daki toplama kamplarında yavaş yavaş ölmesi gibi bilinmeyen yönler de ortaya çıkmış oldu. Ancak kitabı yazıya dökmeye karar vermem, muazzam zenginlikte belgeler barındıran İstanbul Ermeni Patrikhanesi Arşivleri’ne (Kudüs Patrikhanesi’nde saklanmakta olan) ulaşabilmemden sonra oldu. Bu belgelerin tek tek incelenmesi iki yıl sürdü, kitabın yazıya dökülmesi de tam olarak iki yılımı aldı.

Sizi böylesine kapsamlı bir eser yazmaya iten temel sebep ne oldu?

Soykırım sürecinin daha önce ciddi bir şekilde incelenmemiş olduğu çok açıktı. Niyetim, öncelikle, Ermenilerin Anadolu’daki mevcudiyetiyle ilgili daha önce yapılmış olan çalışmaları temel alarak, insanlara ve özellikle de kökenleri buraya dayanan ya da hâlâ burada yaşamakta olan kimselere, 1915 senesinde bu coğrafyada tam olarak ne yaşandığını anlayabilmelerine yardımcı olabilecek bir araç sunabilmek; bunun için de bölge bölge, soykırımın bir coğrafyasını yayınlamak oldu. Çalışmayı yapabilmek için böyle bir mikro tarih gerekliydi. Ancak elbette bu olayı tek başına incelemek olmazdı. Yaşananları, Osmanlı bağlamına oturtarak değerlendirmenin önemli ve gerekli olacağını düşündüm. Kurbanların başına gelenleri ve faillerin niyetini incelerken bir denge tutturulması gerekti. Elimizdeki her türlü kaynağın yanı sıra, tarihsel inceleme süzgecinden geçirerek, kurtulanların tanıklıklarına başvurulması da büyük önem taşıyordu.

Kitap, 2006’da ilk yayınlandığında Fransa’da nasıl bir tepki aldı?

İnsanlar, özellikle de ikinci ve üçüncü nesil Ermeniler, dedelerinin başına ne geldiğini anlayabilmek; başka bir deyişle nasıl ve neden gelip de Fransa’ya yerleştiklerini öğrenmek için kitaba ilgi gösterdiler. Kitapta, pek çok kişinin kendine sorduğu soruların cevabı var. Tarih çevreleri de, Fransız tarih ekolünden yetişmiş bir tarihçinin araştırmalarının ürünü olan bu esere ilgi gösterdi. Öte yandan, eser, belki de bazı tarihçilerin, özellikle de, pek inanılır olmamasına rağmen ve aslında tarihten ziyade propaganda kapsamına giren resmi tezleri destekleme eğilimindeki Türkologların zihinlerini kemiren bazı soru işaretlerini de azaltılmaya yardımcı oldu diyebiliriz.

Araştırmanızı yaparken, Soykırım’ın yaşandığı bölgelerdeki farklılıklar açısından sizi en çok şaşırtan şey ne oldu?

Şüphesiz, aslında 1915 Haziranı ve Ağustosu arasında neredeyse üç aylık bir sürede gerçekleşen tehcirin şaşırtıcı bir düzeyde planlanmış olması. Tehcir edilen kafilelerin düzenlenmesiyle ilgili prosedürler aşağı yukarı benzerlik gösterse de, Anadolu’nun batısından yola çıkan kafilelerin, aile reisinin başında bulunduğu ailelerden oluştuğunu görüyoruz. Oysa, şüphesiz Jön Türklerin önceliği olan doğudaki vilayetlerde, yetişkin erkeklerin ortadan kaldırıldığını, kadın ve çocukların hiçbir korumaları olmadan tehcire gönderildiğine tanık oluyoruz.

Soykırım dönemindeki en önemli aktörlerle, bunların arasındaki ilişkiyi biraz anlatabilir misiniz?

Fail tarafında, bu toplu vahşetin kararını veren, planlayan ve uygulayan temel aktörler, İttihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti Merkez Komitesi’nin on üyesi, yani İttihatçılar olmuştur. Bu kişiler bir yandan Ermenilerin yok edilmesinin temel aracı olarak ve kirli işlerini yürütmek üzere Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa’yı kurmuş, diğer taraftan Tehcirin planlanmasını üstlenecek yerel idareleri de operasyonlarına dâhil etmeyi başarmıştır.

Bu kitabın Türkiye’de, Türkçe olarak yayınlanmasının önemi nedir?

Bu kitap soykırımla ilgili Türkiye’de yayınlanan ilk kitap değil. Ancak kitabın, gerçekleri sadece İstanbul merkezinden değil, vilayetlerden gözlemlemeyi amaçlıyor olması itibariyle, bu vahşetten etkilenen illerde yaşayanların da ilgisini çekeceğini umuyorum. Ne de olsa bu olaylar onların yerel tarihlerinin, hatta aile tarihlerinin bir parçası. İstanbul Ermeni Patrikhanesi makamları tarafından hazırlanan listeler sayesinde, her bir bölge için olaylara karışan temel yerel aktörlerin isimlerine ulaşabiliyoruz: İttihat ve Terakki’nin yerel teşkilatının üyeleri, Emval-i Metruke (Terkedilmiş Mallar) Komisyonlarının yöneticileri, üst düzey memurlar, jandarma subayları, polis amirleri, Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa yetkilileri vs. gibi, Ermeni nüfusunun yok edilmesinde farklı düzeylerde sorumluluğu olan kişilerin isimleri... Bu kişilerin soyundan gelen hiç kimsenin konuya kayıtsız kalabileceğini düşünmüyorum. Ayrıca çalışma, öğrencilerin ve entelektüel okurların da modern Türkiye’nin hangi koşullar altında kurulduğuna dair bir fikir edinmesine yardımcı olacaktır.

Cumhuriyetin kuruluşundan sonra, Türkiye’nin bu konudaki politikasını nasıl değerlendiriyorsunuz?

Öncelikle İttihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti ile Kemalist rejim arasında ideolojik bir devamlılık olduğunu hatırlatmakta fayda var. Kemalist rejim, soykırımdan kurtulan Ermenilerin yanı sıra, Rumlar ve Süryaniler için de suikastlar, sınır dışı etme, tehcir ve vergilendirme gibi farklı yöntemler kullanarak Anadolu’yu etnik olarak homojenleştirmeyi başardı. Öte yandan, modern Türkiye’yi kuran siyasi ve askeri kadroların da, Ermenilerin ortadan kaldırılmasına farklı seviyelerde karışmış olduğu ve ülkeyi yönetenlere bugün bile sirayet etmiş olan tuhaf bir siyasi kültürün doğmasına yol açtıkları da tarihçiler tarafından biliniyor. Bu koşullar altında, Cumhuriyet’in üzerine inşa edildiği bu vahşet geçmişini kabul etmenin yolu, Jön Türklerin arzu ettiği yeni ulusun temellerini sorgulamaktan; dedelerimizin yaptıklarıyla ilgili kendimize sorular sormaktan; kısacası, on yıllardır Kürtlerin başına geldiği gibi, dayatılan kimlik kalıbına oturmayan tüm grupları damgalamaya ve dışlamaya devam eden siyaset çarkının işleyişinin gözden geçirilmesinden geçiyor.

Bütün bunları göz önünde bulundurduğumda, Türkiye devletinin politikasının hızlı bir şekilde değişeceğine inanmıyorum. Belki de değişim, kendisi de pek çok açıdan devlet ideolojisinin mağduru olan sivil toplum kanadından gelecek.

‘Resmi inkâr diplomatik bir şekilde sürüyor’

Hrant Dink’in suikasta kurban gittiği yıl olan 2007, Türkiye’deki Ermeniler için bir dönüm noktası oldu. Takip edebildiğiniz kadarıyla bu yeni dönemi nasıl görüyorsunuz?

Hrant Dink, belli bir grubun yaygın biçimde damgalanmasının yarattığı ölümcül tuzaktan nasıl çıkılabileceğine kafa yormuştu. Söylemleri, hepimizin çok iyi bildiği üzere, zaman zaman Ermeni çevrelerden oldukça sert tepkiler aldı, ancak bununla beraber, bir diyalog (uzlaşma kelimesini kullanmak şimdilik uygun olmaz diye düşünüyorum) fikrinin olgunlaşmasına da şüphesiz katkıda bulundu. Onun öldürülmesi ve öldürülmesinden sonraki tepkiler, şüphesiz en radikal çevreleri bile susturmuş oldu. Ayrıca çok sayıdaki dostunu, bellek mücadelesine; Türkiye’ye ve Türkiye devleti aygıtına derinlemesine nüfuz etmiş olan ideolojinin düzeltilmesine yönelik mücadeleye daha sıkı sarılmaya teşvik etti. Bu elverişli ortam üzerinden, Ermeni ve Türk sivil toplumlarının bazı kesimleri arasında pozitif bir diyalog kurulmuş oldu. Kamuoyunu bilgilendirmek, eleştirel düşüncenin gelişmesine yardımcı olmak ve kamuoyunu Türkiye’de demokrasisinin geleceğinin buradan geçtiğine ikna edebilmek için muazzam bir çaba harcanması gerektiği çok açık.

Türkiye devletinin Ermeni Soykırımı konusunda 2006 yılından beri yürüttüğü politikayı nasıl değerlendiriyorsunuz?

Türkiye’nin Avrupa Birliği’yle müzakere sürecine girmesiyle birlikte, Ermeni Soykırımı’nın tanınması, hiçbir yerde açıkça yazılı olmasa da, şüphesiz ülkenin AB’ye girebilmesi için kaçınılmaz bir siyasi koşul haline geldi. Yetkililer bunun çok iyi farkında ve ülkenin imajını düzeltmek için bazı girişimlerde de bulundular. Bunlardan biri ismi Türkçeleştirilen ve devasa bir Türk bayrağı asılan Ahtamar Kilisesi’nin restorasyonu; diğeri de tarihçilerden, ya da başka bir ifadeyle tam olarak bilmedikleri konuları tartışmaları beklenen tescilli propagandacılardan oluşan bir komisyon kurulması önerisi. İkisi de, resmi inkârı neredeyse biraz daha diplomatik bir şekilde sürdürme isteğini gizlemek amacıyla, karşı tarafın insafına bırakılmış ümitsiz girişimlerdir. Bununla birlikte muhtemelen bazı Türk makamları, verecekleri bir sonraki tavizi -elbette en asgari düzeyde tutulmak kaydıyla- şimdiden düşünmeye başlamıştır. Atılacak olan geri adım Türkiye’deki sivil toplumdan ve dışarıdan gelecek baskıların seviyesiyle doğru orantılı olacaktır.

Doğu’daki bugünkü gerçekler dikkate alındığında, 1915 ile günümüzün devlet politikaları arasındaki benzerlikler ve farklılıklar nelerdir?

Türkiye devleti aygıtında ideolojik devamlılık olduğunu söyleyebiliriz. Şiddete başvurma, siyasi diyalogun olmaması, resmi kalıbın dışında bir kimlik taşıyanların farklılıklarının inatla kabul edilmek istenmemesi gibi sebepler, ‘Kürt Sorunu’ gibi bir meselenin çözümünü karmaşıklaştırıyor. Aylardan beri, Türk makamlarının IŞİD karşısında son derece muğlak bir tutum sergilediğini görüyoruz. Bunun en önemli sebebi, en azından bölgeyi bilen gözlemciler için, Türkiye için Kürt Sorunu’nun, IŞİD’in tüm Orta Doğu için oluşturduğu tehditten çok daha öncelikli olmasıdır. Dönüp dolaşıp 1915’ten beri devam eden bu dışlama ideolojisine; etkili bir diplomasiyle güç bela gizlenen bu tehlikeli milliyetçiliğe geri geliyoruz.